Welcome to Warning Track Power, a weekly newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

If you don’t already subscribe (for free), please consider doing so today. And if you enjoy WTP, go ahead and share it.

For most of my adult life, I’ve been fortunate enough to find myself planted at the intersection of baseball and wine. Arrival at those crossroads used to be a more of a novelty, an affair born out of the randomness of the population.

There was the late Rusty Staub, whose gregarious nature and generosity made him a delightful ambassador of both the game and the grape. I fondly remember speaking with him on a handful of occasions during my time at Wine Spectator, mostly while covering his efforts in the charity wine market.

His work shortly after 9/11 to raise money for the families of fallen first responders has always stuck with me. His compassion and sense of purpose were as honorable as they were heroic.

Staub, in many ways, was the godfather of baseball players appreciating wine as a serious pursuit.

Prior to the 2002 season, I interviewed Hall of Famer Mike Piazza, whose wine knowledge extended well beyond pointing to the most expensive bottle on the list and ordering it.

Meanwhile, wine collecting was infiltrating Major League clubhouses. It had to be; once one player caught the fever, he had teammates to share with.

When I came on board with the Padres, my background and knowledge allowed me to become more comfortable interacting in the clubhouse because there were plenty of players — Piazza, Shawn Estes, Glendon Rusch, all of whom played for the Mets in the early 2000s — who wanted to talk wine. Coaches, too, were willing participants.

I was able to make the obvious natural transition from wine journalist to baseball ops staffer because, simply, wine opened doors. I met Kevin Towers while I was an editor at Wine Spectator.

It’s uncanny how so many baseball people who were once part of the Padres organization are now involved in the wine industry.

Dodgers manager Dave Roberts and former Giants slugger Rich Aurilia formed Red Stitch Winery and released their inaugural vintage in 2007, which was the season that both men were first teammates in San Francisco (managed by knowledgeable wine drinker Bruce Bochy).

Roberts and Aurilia both had brief stints as Padres.

More recently, former Angels teammates Vernon Wells and Chris Iannetta — neither of whom played for the Friars — started making wine together at their Napa Valley winery JACK.

But it took a pandemic and some creative thinking by a philanthropist who once hit 50 homers in a season to augment the impetus of the winemaking ballplayer.

Greg Vaughn, who spent the majority of his Major League career in the city where “The Beer Barrel Polka” is proudly played, rolled out some barrels of his own recently with the help of E2 Family Winery in Lodi, California.

Red Stitch and JACK both offer bottlings that sell for $100 or more, placing them in — or at least around — the company of the Napa Valley elite. For Vaughn, the scope was different.

“I want to make a wine that’s accessible and affordable to the public,” he says.

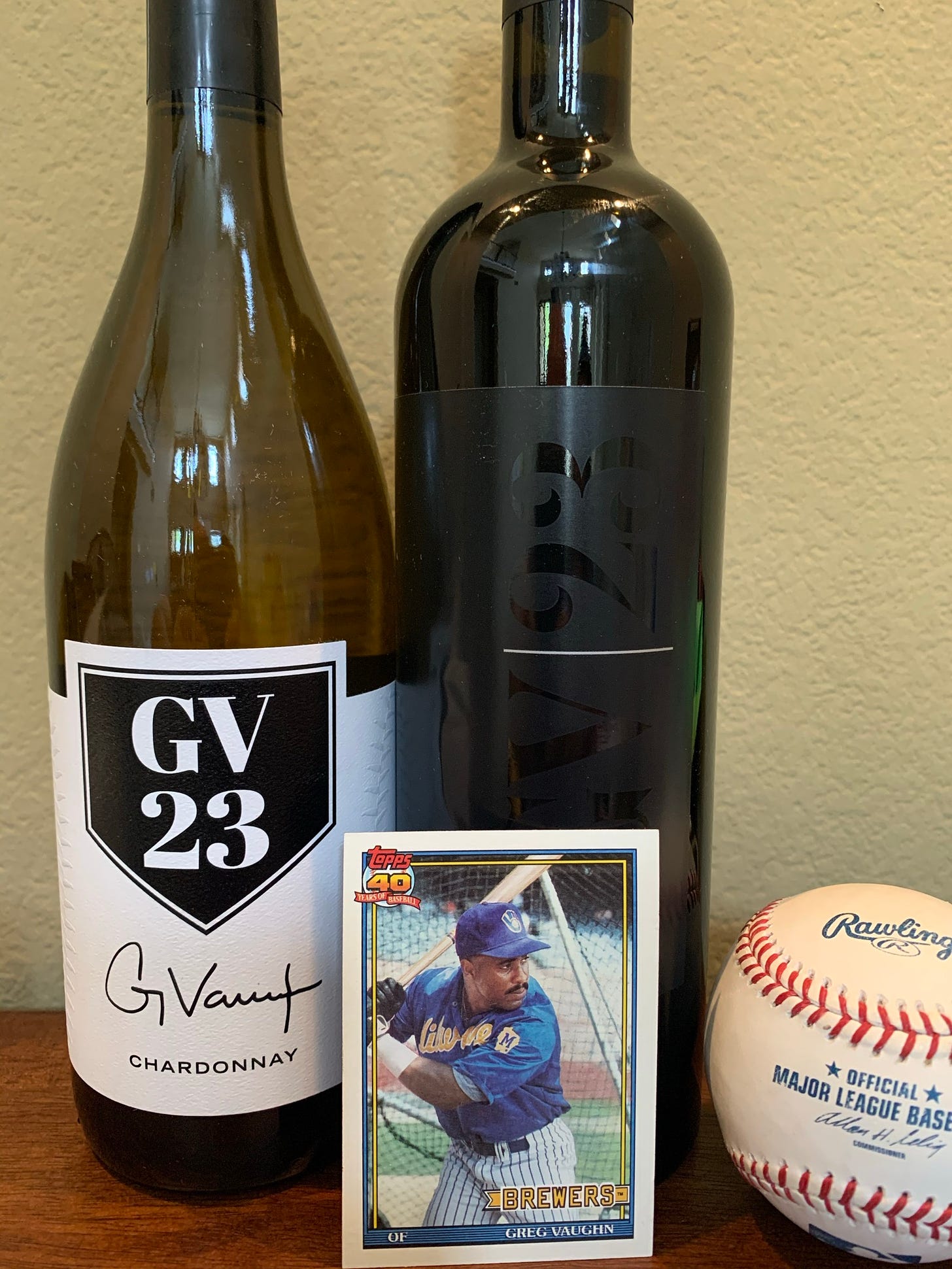

Under the label of GV23, Vaughn — along with winemaker Brett Ehlers — has released a 2017 Chardonnay and a 2016 Cabernet Sauvignon.

The wine-producing window opened once other doors closed. Vaughn, whose Vaughn’s Valley Foundation in his hometown of Sacramento supports the local community, needed new fundraising streams after the pandemic put a halt to golf events and comedy shows.

“Community was always important,” he says. His body of work in support of the local area speaks for itself.

After the diagnosis of his son Cory with Type 1 diabetes “rocked my whole family’s world,” Vaughn scrupulously educated himself about the disease. His foundation was born out of love, knowledge, and a desire to make an impact.

Soon, he realized there was more than the local diabetes community that needed help. That’s when he created scholarships for non-athletes below the poverty line.

Vaughn’s work in northern California continued where it was needed — turkeys for Thanksgiving, bicycles for Christmas.

During the pandemic, the foundation provided 10,000 Chromebooks and 20,000 whiteboards. “For kids that look like me,” Vaughn said, “distance learning was a challenge. Some school districts didn’t have the proper tools.” Vaughn made sure they did.

So when a local winery in Lodi provided the opportunity to create his own label, Vaughn dug in.

“I have to come out and see it from start to end because I don’t want to endorse something I don’t know much about,” he confesses. Vaughn worked with the harvest team, and he helped create the labels. He worked with Ehlers to create the final blends of his wines.

“I wanted the whole experience of the process.”

The 2017 Chardonnay is a straightforward California expression of the grape. The presence of oak is apparent through the welcoming aromas of creamy vanilla and melon. The wine has plenty of acid to stand up to food, and toasted marshmallow notes add depth that lingers.

The 2016 Cabernet Sauvignon softens after opening, so don’t let the initial impressions of alcohol deter you. The toasty vanilla nose yields to notes of spice and dark berries. One sip of the wine and I wished I had a burger to go along with it. This a great wine to enjoy around the grill in the summer, and it has the structure to pair with steak, grilled veggies, or a nice cigar.

Both of these wines are strong representations of the Lodi Wine Country viticultural area. In Europe, winemakers often speak of terroir, a French term that doesn’t translate perfectly into English but loosely means “a sense of place.”

When enophiles talk terroir, they’re referring to how the soil, the climate, and the land’s history are expressed in a wine. In California, where wines are stylistically different than those of traditional “old world” winemaking regions, terroir takes on new meaning for me.

With Vaughn’s two wines, I think of the motivation that went into the project, the courage it took to enter the marketplace, the beneficiaries of the initiative, and — of course — the former Silver Slugger inserting himself into all aspects of the wine’s lifecycle.

At $30 per bottle, these wines aren’t at everyone’s price point, but they deliver quality and support the fight against Type 1 diabetes as well. (Did I just slip a couple wine reviews into this space? Fantastic.)

Vaughn made 60 cases of wine to see what would happen. As the bottles are being purchased around the country — resold in ballparks in Cincinnati and Milwaukee already and also enjoyed at home by enthusiastic consumers — the next order is going to have to be larger.

A Merlot and a rosé are on the way, too. (You can learn more and purchase here.)

“It allows me to be involved with baseball in a different way,” Vaughn said. Hey, one man’s substack is another man’s wine label.

All profits from wine sales go back into the foundation.

Vaughn is currently developing a center in Sacramento where kids can “get off devices and be in touch with society.” There will be pickleball courts and academic opportunities. He’s creating a space where doctors, lawyers, teachers, and firefighters alike can serve as role models.

As an African-American in the winemaking world, Vaughn adds to his own portfolio of leadership by example.

“I was blessed to play a sport, and I’m blessed to touch lives also.”

Thank you for reading Warning Track Power. Subscribe now to have WTP delivered to your inbox every Thursday — wine list available upon request.

Great piece, Wine Dog!