Welcome to Warning Track Power, an independent newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

Record producer Rick Rubin recently shared a story while a guest on the Freakonomics podcast (and probably a few others) about becoming unexpectedly emotional while watching the 2017 documentary film “AlphaGo.”

Go is a 3,000-year-old Chinese board game; with a 19-by-19 board and 361 squares or “points,” the potential moves for this two-player game far outnumber those of chess.

The documentary is named for the artificial intelligence program, AlphaGo, that has been built and trained to play the game.

As Rubin says on the podcast: “Go is considered the most difficult game for AI to conquer because there are more possible combinations in the game than there are grains of sand on the beach on the planet. So it was believed if the machine could ever beat the human, the world changes.”

During one of the matches, the computer makes a move that humans considered, or assumed was, a mistake. The television commentators say as much.

Well, the computer — the artificial intelligence engine — wins that match and the entire competition against a Grand Master of the game.

Rubin explains:

“And what I came to realize was the computer didn’t win because it was smarter than the man. The computer didn’t know more than the man. The computer knew less. The computer wasn’t steeped in the lore of the game. All the computer knew were the rules. So it did a move that no seasoned player would ever do because seasoned players are taught by seasoned players, and the seasoned players are following whatever the accepted version of playing the game is — not the rules of the game, but the socially acceptable way to play the game. When he made the move that ended up leading to him winning the game, the Grand Master got up and left the table. It wasn’t because you’re not supposed to do that. It’s because everyone thought you can’t do it; when it turns out you can do it.”

Sound familiar?

As I tuned in to Tampa Bay Rays games for a couple weeks at the end of last month, I thought a lot about Rubin’s assessment of the computer that was trained in the rules, just the rules, of Go.

Social Norms vs. The Rules

Major League Baseball has been revolutionized by an iconoclastic generation that has no nostalgia for playing pepper. Its behaviors are more about training AlphaGo than swinging a fungo.

The socially acceptable version of baseball was an exploitable soft spot for a new wave of baseball operations executives, powered not by artificial intelligence but by innate intelligence and a suite of new tools.

What amazes me about Tampa Bay is that the organization has the discipline to block out the rest of society. We all know that limited financial wherewithal requires that the Rays seek incremental gains more creatively; the commitment not just to survival but success is remarkable.

There’s a starting pitcher, but he only throws one inning. Rubin’s “seasoned players” — traditional baseball folks and casual fans in this instance — expect their starter to go deep into a game. For the Rays, the construct of the starter was merely societal convention.

Tampa Bay followed the rules, not the social norms. Openers replaced starters. Defenders overshifted to areas of the field where data determined that the ball was most likely to be hit (until MLB rewrote rules).

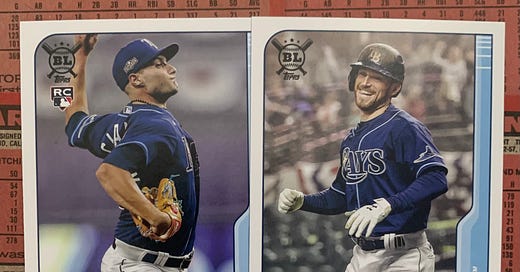

The 2023 Rays, 49-22 after last night’s win in Oakland, represent everything that the organization’s baseball operations group does right. The roster includes a top international amateur signing (Wander Franco), their own first-round draft picks (Josh Lowe, 2016; Shane McClanahan, 2018), players acquired through savvy and often under-the-radar trades (Randy Arozarena, Yandy Diaz) or trades in which the Rays appear to have identified something about the player that only they appreciate (Jose Siri, Christian Bethancourt, Luke Raley), and the occasional free agent signing (Zach Eflin).

The Rays staff wouldn’t have lasted long in 17th-century Salem. Their brand of witchcraft has turned a light-hitting elite defensive centerfielder into a home run hitter. Jose Siri, who still ranks as one of the fastest players in MLB with one of the strongest outfield arms, is also hitting balls on the barrel more frequently than almost all of his peers. At the same time, he’s swinging, missing, and striking out more frequently than almost all of his peers.

Tampa Bay does a great job of accepting players for who they are and developing them into the very best versions of themselves. We should all be so lucky as to spend a season under the care of the Rays.

Siri is a great example of such nurturing. He strikes out in more than one-third of his plate appearances. He always has at the big league level. Moreover, he rarely walks. Not too long ago, that combination was the kind of red flag that inspires after-school specials — don’t get in the car with Jose!

But the current model of Siri has already hit 12 home runs, the same amount as Julio Rodriguez, one more than Paul Goldschmidt, and three more than Vladimir Guerrero. When Siri does make contact with the ball, he makes it count. I’m not sure there’s another competitive organization in the league today that would provide that player the time and space to develop. Or is it change?

Development vs. Change

No apparent secret reveals itself after both watching their games and digging into the stats. The Rays, though, have made me consider the difference between traditional player development — the process during which a talented young player should mature and refine his game through coaching and repetition — and blunt change.

Warning Track Power is a reader-supported project. Free and paid versions are available. The best way to support us through a paid subscription. It helps us keep the needle on the record.

My sense is that the Rays understand how to change a player — whether that’s in regards to his thinking and mindset or something physically in his approach, mechanics or usage — better than any other team. They also seem to believe — and commit to — individual coaching and instruction; the gains that many players realize once they wear the uniform aren’t likely to happen serendipitously around the batting cage.

Take Me To October

The Rays came down to earth a bit after their 27-6 start. They are 22-16 since then, yet their lead over the Orioles in the AL East has grown by half-a-game during that span. It’s hard to see them running away with the division, and it’s also hard to see them not winning it.

“When you know more, you know what’s impossible,” Rick Rubin says during the Freakonomics podcast. Rubin was still a student at NYU when he produced Run-DMC’s “Raising Hell.” He benefitted from the freedom of not knowing too much about producing records. (I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that my grandmother reluctantly bought me that cassette after her attempt to redirect me to Air Supply’s Greatest Hits was thwarted. My parents already owned it, I assured her.)

For Rubin, it’s the creative process; for the Rays, it’s baseball strategy.

“Knowing what’s impossible doesn’t help you do the impossible,” he says. “You have to believe in something that’s impossible to allow it to come into existence.”

In Tampa Bay, they believe in the impossible.

WTP offers free and paid subscriptions. Sign up now and never miss a word.