Welcome to Warning Track Power, a weekly newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

The defending World Series champs trailed by 18 in the ninth inning.

Meanwhile, in the Bay Area, the Moneyball A’s were well into a 20-game winning streak. The implementation of analytics that largely defined the movement — one that would change the game forever — still hadn’t been celebrated in popular culture.

Analytics, however, were not needed to know that back in Arizona — down 18-0 with only three outs to go — the Diamondbacks had absolutely no chance of winning.

So when the Dodgers came to bat in the visitor’s half of the final frame on September 2, 2002, they faced a player that opposing players had previously only encountered after safely reaching first base.

Mark Grace, the three-time All-Star and four-time Gold Glove winner, took his position 60-feet, six-inches away from home plate for the first and only time in his career.

He retired the first two batters he faced before surrendering a home run to Dodgers catcher David Ross. It was the first homer of the young catcher’s career. (In fact, the only two hits Ross collected in the 2002 season came during that game.)

Twenty years later and now managing the Cubs, Ross handed the ball to the same position player three times in a two-week span earlier this month. In those games, entering the ninth inning, the Cubs trailed by seven, 13, and 11 runs.

MLB instituted a rule prior to the 2020 season that requires teams to be separated by at least six runs in order for a position player to pitch (before extra innings). Teams across the league have enthusiastically replied: Challenge accepted.

After there were 90 appearances on the mound by position players in 2019, a new standard was set last year: 95.

The pace this season suggests last year’s record won’t last long, especially when managers deploy three position players to pitch in one game, like AJ Hinch did for the Tigers last Wednesday. A one-time novelty is evolving into a near-nightly occurrence.

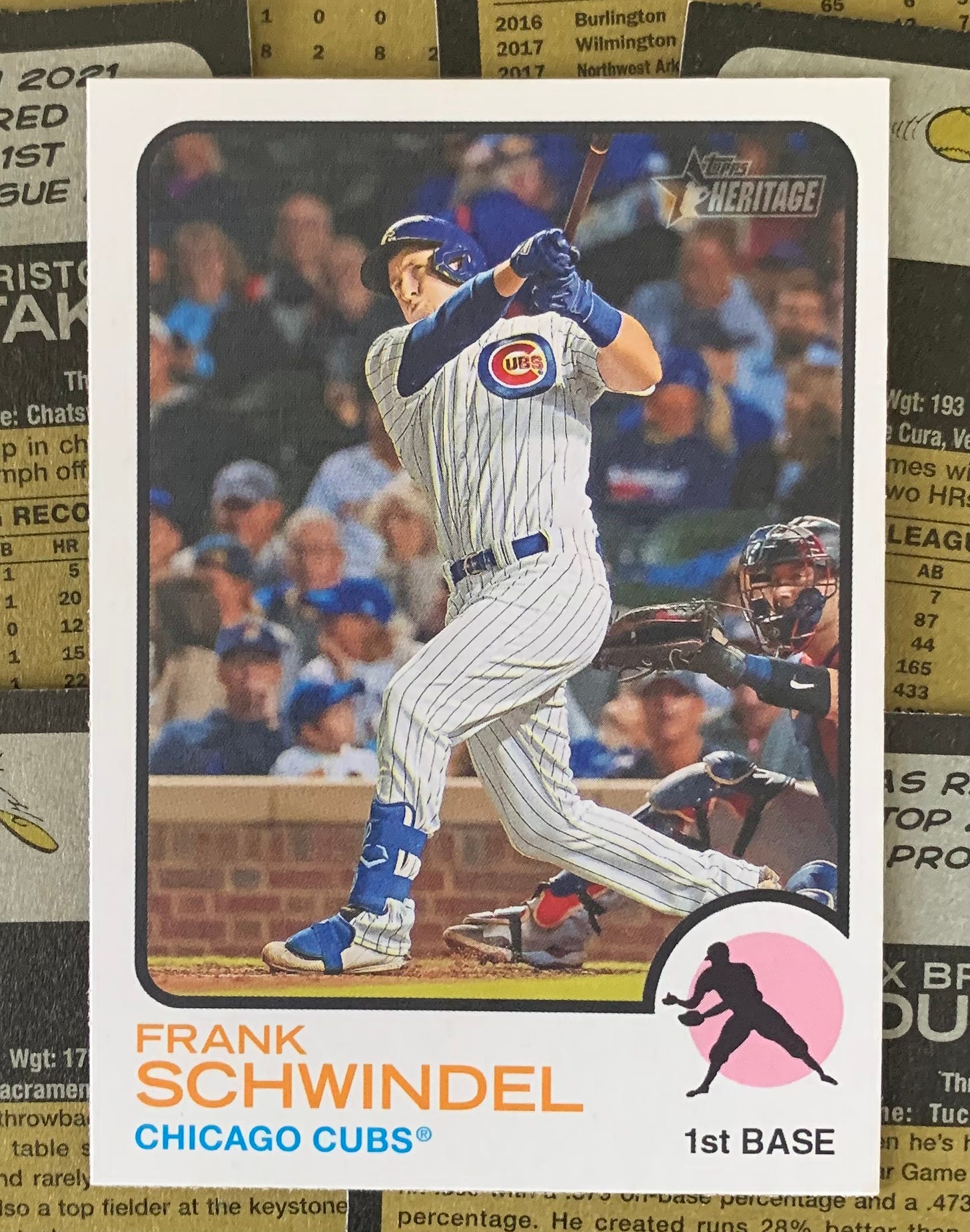

The Cubs garbage-time hurler, Frank Schwindel, was placed on the Injured List last week with a lower back strain. Often, not too many years ago, coaches and management would worry about a position player hurting himself while pitching. Players would talk about how sore they felt in the aftermath.

Today, position players are being advised by coaches to go slow. The slower you throw it, they’re told, the sooner you get outs.

Schwindel, apparently, is a good listener. During his outing against the Yankees, he unleashed a 35 MPH fastb…, uh, pitch. And catcher Kyle Higashioka took it deep.

Even with Frank the Tank and his 18.00 ERA on the shelf, the parade of position players toeing the slab continues. Does it jeopardize the integrity of the game, or is it simply good strategy? Or maybe both?

Here’s the catch: When MLB set clear parameters around when a position player could be used, they took the folly out of it. The overt creation of a rule begs teams to identify and act upon potential advantages.

Additionally, managers have to think about tomorrow’s game; sometimes it’s strategically sound to preserve a bullpen for a day when every pitch might matter.

With many starters today expected to face fewer batters, pitching staffs are constructed differently. The long-man’s spot in the bullpen is no longer what it was.

“We used to call it a 7-11 pitcher back in the day,” says Mike Fetters, former MLB reliever and current bullpen coach of the D-backs. “It was the guy who only got in when you were down by seven or up by 11.”

Perhaps it was the backdrop of the Stanley Cup playoffs, but I started thinking about the Emergency Backup Goalie (EBUG) in the NHL. This is a role and a rule that I find as bizarre and fascinating today as I did the first time I ever heard about it.

In every NHL city, in accordance with Rule 5.3, there is an individual designated to attend every home game. He’s not on the roster, but occasionally he practices with the team. He most likely has a full-time job that has nothing at all to do with hockey.

In the event both goalies on either team succumb to injuries during a game, this person is called upon to suit up and take the ice.

The EBUG puts on the pads, pulls on the jersey (or sweater) and hunkers down between the pipes — in the NHL! (For a feel-good story about the most recent EBUG, Tom Hodges, click here.)

Imagine this type of arrangement in the NFL or NBA. Imagine it in baseball. Is this a Canadian way of life?

Look, no team wants to find itself trailing by a Let’s-Stick-Manny-Alexander-On-The-Mound amount in any game. You could argue that being down by six in the ninth is punishment enough. But I find six a funny threshold.

Twice this season, visiting teams have erased six-run deficits in the top of the ninth. Both of those teams went on to win, and no position players found themselves, well, out of position. (Coincidence that those two winning teams are managed by Buck Showalter and Terry Francona?)

So what is the right protocol? Should teams be given the ability to forfeit? Should the threshold for triggering the the relief pitcher exception be increased?

Let me know what you think in the comments below.

While the novelty of this position player pitcher thing used to be fun, it’s clearly gotten out of hand. I get wanting to preserve a pitcher in a game you think you can’t win (or lose). But I remember one time there was this college game where one team was down 22-9 going into the 9th, and they tied it up, scoring 11 of their runs with 2 outs, no less. Crazy things can happen. Watching position players on the mound now is no longer fun. I want teams fighting till the last out.