Welcome to Warning Track Power, a weekly newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

In Monday night’s Wild Card victory over the Arizona Cardinals, safety Eric Weddle came out of retirement to suit up for the depleted Los Angeles Rams’ defense. He was on the field for 19 snaps, accounting for 34% of the defensive plays for his team.

It had been 750 days since Weddle’s last game in the NFL, quite a layoff for any athlete regardless of the sport.

Sometimes, though, when the depth dries up, organizations have to expand their scope.

In 2015, just before Opening Day, I received an email from the mothership in Tampa Bay. All Rays pro scouts were asked to provide the names of any potential free agent first basemen who would be good (or temporarily serviceable) candidates to add to the Major League roster immediately.

I had been with the Rays for about one month at that point, and I was eager to demonstrate value.

My candidate had retired at the end of the previous season — hardly an Eric Weddle situation. The concern for me was geography.

Lyle Overbay and his family live in the Pacific Northwest. To convince a happily retired family man to lace ’em up again and play for the team farthest from his home seemed like a too big of a stretch, even for a solid defensive first baseman.

Overbay and I recently laughed about the fact that nobody from the Rays ever called him, and nobody in the scouting department replied to my email.

Out of curiosity, I asked him how long he thought it would’ve taken him to be ready to hit big league pitching had he gotten a call.

“Whew,” he began — a response not likely to generate much confidence from evaluators. “That next year [after retirement], I was still fresh and in baseball shape… still working out.”

He paused. “That’s a tough one.”

Overbay then guided me through his offseason preparation schedule. He, like most position players, started swinging a bat in late November or early December. He’d increase the intensity and focus in January and February, leading into Spring Training.

Once exhibition games begin, he’d start to think about how he felt at the plate. Overbay felt he needed two weeks of at bats to get locked in, a sentiment that Jeff Bagwell also shared with me last month.

Going from the couch to live competition, however, is a different beast. Overbay figured that had the Rays expressed interest in him around Opening Day 2015, it would have taken him three to four weeks of seeing pitches to begin to get comfortable, and then another couple weeks for his feel to return.

Given the immediate nature of their need, it makes sense that Tampa went with someone who was already active in their organization.

If the phone rang today?

“Now,” Overbay said, “it would take me about three years.”

Part of why I felt compelled to recommend Overbay in 2015 is because of what I watched him do in 2011.

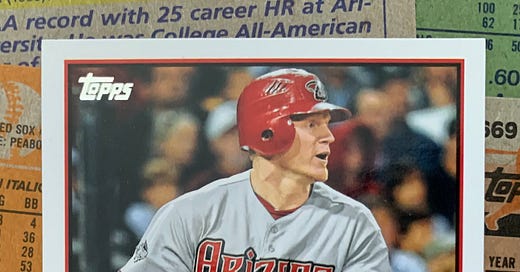

That Diamondbacks vintage opened the season with Juan Miranda, Xavier Nady, and Russell Branyan sharing first base responsibilities. (This is probably a good time to remind you that the 2011 D-backs won 94 games.)

On August 12 of that year, with Miranda and Branyan already off the roster, Nady was hit by a pitch and broke his hand. That left Paul Goldschmidt, not even two weeks into his big league career, as the lone first baseman on the active roster.

Earlier in the month, the Pirates had released Overbay. I still remember the way that night unfolded immediately after we learned that Nady’s hand had been broken.

We needed somebody. We needed a healthy body. We knew that Overbay was available, and our scouts thought he could contribute. We also knew that he would be a positive influence in the clubhouse.

Before the end of the game, Kevin Towers and Overbay’s agent, Steve Hilliard, had reached an agreement. (I believe that Hilliard told KT that Overbay was at home, on the couch, watching TV.) Two days later, Overbay was in uniform.

Though it took a bad break, we had serendipitously signed a mentor for Goldschmidt.

There’s a certain kind of magic that exists for teams in great seasons where availability and opportunity collide to wash away the residue of misfortune. It’s important to appreciate those moments because there is another side to that coin.

Overbay and Goldschmidt were teammates for the final quarter of the regular season, but it wasn’t until the postseason that the veteran truly understood the rookie’s potential.

“Seeing him do what he did in the playoffs really stood out to me,” Overbay said about the now six-time All-Star and four-time Gold Glove winner. He mentions an opposite field double that Goldschmidt hit off Zack Greinke, who was in his prime in 2011. “You don’t do that against Zack Greinke.” But Goldy did.

Overbay recalls the damage Goldschmidt did against many of the league’s top pitchers, including former Giants Matt Cain and Tim Lincecum.

“You get your hits off the four-five starters, not the one-twos.”

When Overbay re-signed with the D-backs in 2012, he made sure to first call Goldschmidt. Overbay didn’t want his presence to distract the young player.

“I think the hardest thing to do in the big leagues is to start a season,” Overbay offered, reasoning that when a player is called up midseason, he’s usually hot and capable of hitting any pitcher.

Indeed, Goldschmidt struggled to a .193 batting average through the first full month of the 2012 season. “It will get easier,” Overbay reminded him. It quickly did, and Goldy finished the first half hitting over .300 with a .920 OPS.

We are entering a critical time in labor negotiations. The two parties have made little progress towards a new CBA, and the risk of a delayed Opening Day is imminent.

When Overbay said that the hardest thing to do is to start a season, this isn’t what he meant.

Thank you for reading Warning Track Power. Subscribe now to have WTP delivered to your inbox every week without interruption.

Another fantastic piece!