For the second consecutive year, a Hall of Fame voter submitted his ballot with only a single eligible player receiving a vote. Pitcher Billy Wagner, his candidate both this year and last, fell five votes short of election. In a year in which three players were elected, it made me curious: Was voting only Wagner some passive-aggressive display of performance art? Does the voter want to be questioned publicly?

Or does it even matter?

We don’t have to like it. I don’t. But I’m not here to argue a voter’s right to cast his own ballot, no matter how absurd.

I’ll stick to what I wrote last year: The Hall is a museum.

In that one voter's exhibit, there's only Billy Wagner. When you visit the Met or the MoMA, you trust in the curation — so much so that you may not even consider it. When you see a painting you don’t like, is there any thought given to other pieces that should be on the wall instead?

You don’t have to like every piece and you don’t have to like every Hall of Famer; maybe Joe Mauer is your abstract expressionism. Perhaps Rabbit Marinville is your gothic. Willie Mays may be a da Vinci, and Joe Mauer could be the work of a Dada artist. And we still haven’t talked about what’s presented in the Smithsonian or the UFO Museum or in Amsterdam’s Torture Museum.

The Baseball Hall of Fame is just different. The Plaque Gallery is an exhibit curated by voters — curation by election. Some days, the voters make for an oddly constructed oligarchy.

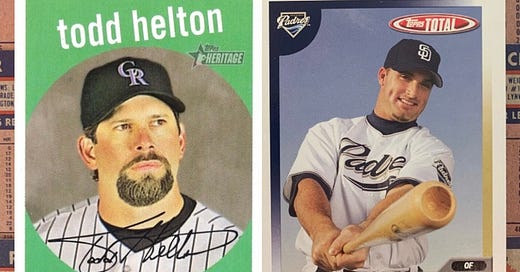

Before I mixed too many metaphors and typed myself too far over my head in art history, I reached out to Mark Sweeney, a teammate of Todd Helton, one of the recently elected members of the Hall of Fame Class of ’24.

Sweeney played for seven teams, all in the National League, during a 14-year big league career. Prior to the 2003 season, he signed with the Rockies as a free agent and ultimately spent two years in Colorado. He arrived in time to have a front-row seat for the tail end of peak Helton, two seasons in which the first baseman posted an OPS of 1.088.

Times were changing in the Mile High City. Hall of Famer Larry Walker and the Blake Street Bombers were on their way out. Helton represented a new era of Rockies baseball, a span of time that included the team’s unlikely (or magical, depending on where you’re from) 2007 run to the World Series.

Five years prior to having Helton as a teammate, Sweeney went to work with Tony Gwynn every day.

“The perspective of watching Tony, and then to watch another hitter not give in and not give an at-bat away was a treat… [Helton] feasted on everybody, and it was phenomenal.”

Sweeney recalls one time when Helton was facing one of the league’s best pitchers. With the count even, he drilled a ball down the right field line. Off the bat, the Rockies players watching from the dugout thought it could be gone. Alas, it was just foul.

By the time the ball landed, Helton had almost reached first base. He took his time walking back to the batter’s box. Sweeney knew his teammate was preparing for the next pitch: “He was always in deep thought when he was playing.”

The following offering to the lefty was a changeup off the plate, almost in the right-handed hitter’s box. “You could tell he was fooled a little bit,” Sweeney offers. For most players, that spells trouble. For Helton, it meant a rocket down the left field line for a double.

Sweeney’s reaction? “I literally went upstairs [to the video room] and I said, ‘I need to see these pitches.’”

It’s a pretty good sequence for a pitcher: a cutter up and in that’s pulled foul followed by a changeup away.

“You don’t see that many people with that kind of bat control who could handle all kinds of velocity… That’s different. That’s completely different,” says Sweeney.

Of course, any player who called Coors Field home comes under additional scrutiny from the baseball community at large. Helton hit about 62% of his 369 career home runs at home. Sweeney admits that the home ballpark also allowed for more doubles in the gaps. “The guy was line to line, and you saw that in a select few.”

In the ’90s and early 2000s, hitting backgrounds — the batter’s eye — still varied in quality from stadium to stadium. Sweeney emphasizes that one of the real benefits of Coors Field was that hitters could see the ball very well. It wasn’t like that at every ballpark, even 20 years ago.

“Now everything is almost perfect. Back in the day, you didn’t complain.”

Sweeney wasn’t shy about taking advantage of what his home ballpark offered: In 2004, he slugged an otherworldly .700 at Coors Field. (Helton slugged .693 at home that season.)

But with the benefits of hitting at Coors Field came the physical challenges of playing in altitude. Sweeney admires how Helton showed up ready to play every day.

In his first 10 full seasons — from his rookie year of 1998 through 2007 — Helton never played fewer than 144 games. He averaged 154 games played during that span, a time before the universal DH. Perhaps the statistics I’m most excited to see immortalized are his strikeout and walk totals. Helton drew 1,335 bases on balls in his career and struck out only 1,175 times. (His strikeout rate was 12.4% compared to the MLB average of 17.5% during his career.)

My belief is that if Major League Baseball is going to be played in Denver, we can’t punish the guys on the home team. As Sweeney reflected upon Helton’s career, he arrived at consistency. Todd Helton earned enshrinement through consistency.

“He played the game like he had never done anything well in it,” Sweeney says, “and that was his motivation.”