Welcome to Warning Track Power, a weekly newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

At this point in our relationship, I hope you know that I’d never subject you to several hundred words about the folly of Hall of Fame voters.

Instead, while waiting for Vince McMahon to open his own museum behind an inaugural class of Rose, Bonds, Clemens, Sosa, and — sure, why not? — Canseco, I caught up with a scout who had a role in drafting three legitimate first-ballot Hall of Famers.

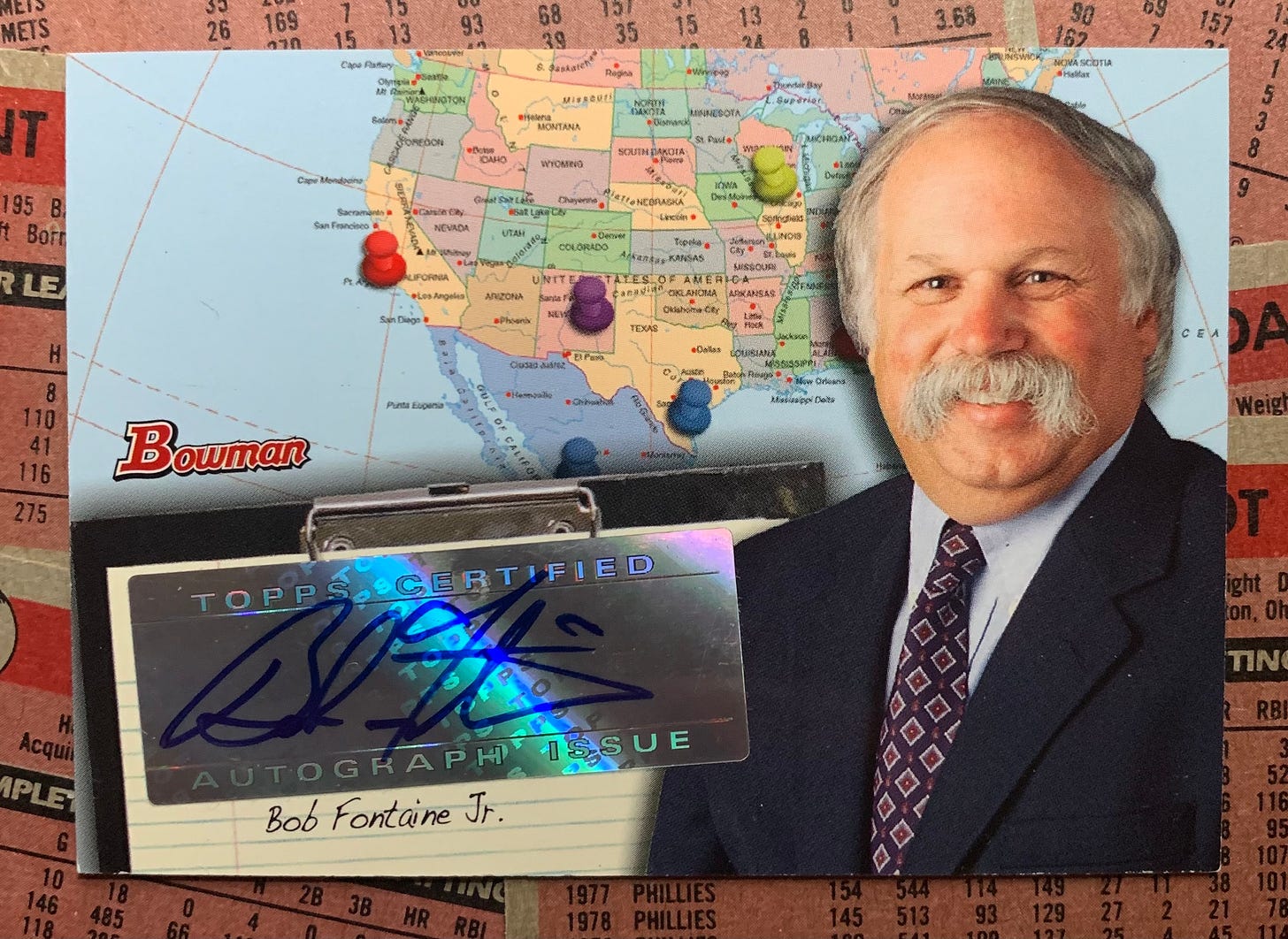

Bob Fontaine Jr., was born into baseball. His father, Bob Sr., was a baseball lifer who had a five-year minor league career (and lost a few years while serving in World War II) before scouting for two decades. In 1969, Senior became the Padres first director of amateur scouting, and he ultimately served as the team’s GM in the late ’70s.

So, as they say in the industry, Junior had good bloodlines.

He followed in his father’s footsteps and enjoyed a 48-year career in professional baseball, including stints as amateur scouting director for the Angels and the Mariners and farm director for the White Sox. Bob, Jr. was instrumental in drafting and signing more than 100 big leaguers, including Tony Gwynn, Ozzie Smith, and Randy Johnson.

Bob Fontaine Jr. has forgotten more about baseball than we’ll ever know.

Fortunately, his story, In Search of Millionaires (The Life of a Baseball Gypsy), written with Taylor Ward, covers his career from the very beginning, as a 19-year-old scout with the Padres in 1973, through his time running the draft for the Mariners.

I got to know Fontaine a bit about five years ago when he, Bill Bavasi and I met one day in a midtown Manhattan coffee shop — Ground Central on E. 52nd St. — to record what was essentially a demo for a podcast. As I was reading In Search of Millionaires, I came across a couple stories that sounded familiar. It took me back to the three of us huddled around a single microphone, romanticizing over old scouting stories.

One of Fontaine’s strengths as a storyteller is the effortless way in which he weaves his wisdom into every tale. For him, it’s merely carrying on a tradition that he benefited from years ago.

“I can’t tell you how far a jug of scotch can go in the learning process,” he says, alluding to the evenings with veteran scouts from whom he learned the finer points of his profession. The book includes the story of Fontaine’s first — and only — night of drinking Beefeater martinis as well as the memory of the following night, when the desire to impress his more seasoned peers had him posting up again — and sticking to beer.

That story warmed my liver. Some of the best nights I had in baseball are ones I wish I could remember.

Then there was that dinner in New Orleans at Elmwood Plantation in 1975:

When the bill came, I nearly fainted. My cut was $75, which was the equivalent of over seven days’ meal money… for the next seven days I was eating 18 cent hamburgers.

The book is a travel journal, scouting handbook, and history lesson all in one. While Fontaine wrote it for his kids, who have since gained a greater understanding of what their father did for all these years, he felt a sense of urgency to document so many names and events.

“Let’s face it,” he says, “the direction the scouting industry has gone is completely different… I tell you what, you’re talking human element here; you better have some humans involved in the process.”

What Fontaine gives to the game is a network of bridges connecting Branch Rickey, Buzzie Bavasi, and Tom Greenwade (the scout who signed Mickey Mantle), to Jack McKeon, Ozzie Guillen, John Kruk, Jim Abbott, and Tim Salmon. There are hundreds of fuel stops, rain outs, and happy hours along the way.

I brought up Rene Gonzales, a versatile and steady defender whom Fontaine scouted while he was the West Coast supervisor for the Expos. Fontaine needs only to be prompted with a name to theorize over the historical significance of such a player:

“Here’s a case where he was an outstanding defender from day one — he could play [in the big leagues] with his glove right then. And the glove allowed him time to become a pretty respectable Major League hitter. Nobody was judging his batting average or how many home runs he hit. They were judging that this guy is so good defensively, he’s saving runs for the team with his defense, which got him enough at bats to become a pretty decent hitter.

“You used to see that a lot with catchers. If you could catch and throw, you would get the time to play enough to usually become a decent hitter and maybe develop a little power, where you might not get that chance at another position where they’re looking for the offensive potential right off the bat. I think things have changed now that at almost every position on the field, they expect you to hit right off. And defense isn’t looked upon, especially at catching and shortstop, as important as it used to be.”

Fontaine and I had this conversation over the phone. It leaves me wondering what’s possible with a jug of scotch.

Thank you for reading Warning Track Power. Subscribe now to have WTP delivered to your inbox every week without interruption.

Great guy!