Zamboni in the Bullpen

The story of a neighborhood flag football game between the Rockies and the Avalanche

Welcome to Warning Track Power, a weekly newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way. If you don’t subscribe already, join hundreds of baseball fans that receive every edition directly in their inbox.

This was the rematch.

The first game, one week prior, was a blowout. The baseball players used the vertical game to make quick work of the boys from the NHL. With a pitcher as their quarterback, it shouldn’t have been much of a surprise.

We’ve all seen baseball players throw a football around, run a few routes in the outfield. Can’t say I’ve ever seen that happen at morning skate.

Take them off the ice and a lot of hockey players don’t move very quickly. Really, it’s not a skill essential to their game. How are you on skates?

How are you on skates while following a puck and accounting for opposing skaters who see bullseyes on your chest?

So let’s all agree that it’s okay that some hockey players are not designed to excel on unfrozen surfaces.

But after suffering a lopsided defeat in the first game, no one should have expected a group of fierce competitors to walk away quietly.

The humiliation was still fresh. Who knows how a flag football defeat can weigh on professional athletes? Who knows how much real estate three relievers and a light-hitting infielder occupied in the minds of a future NHL Hall of Famer?

In advance of the second meeting, the hockey players made an adjustment.

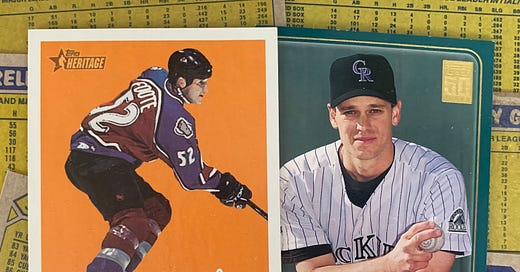

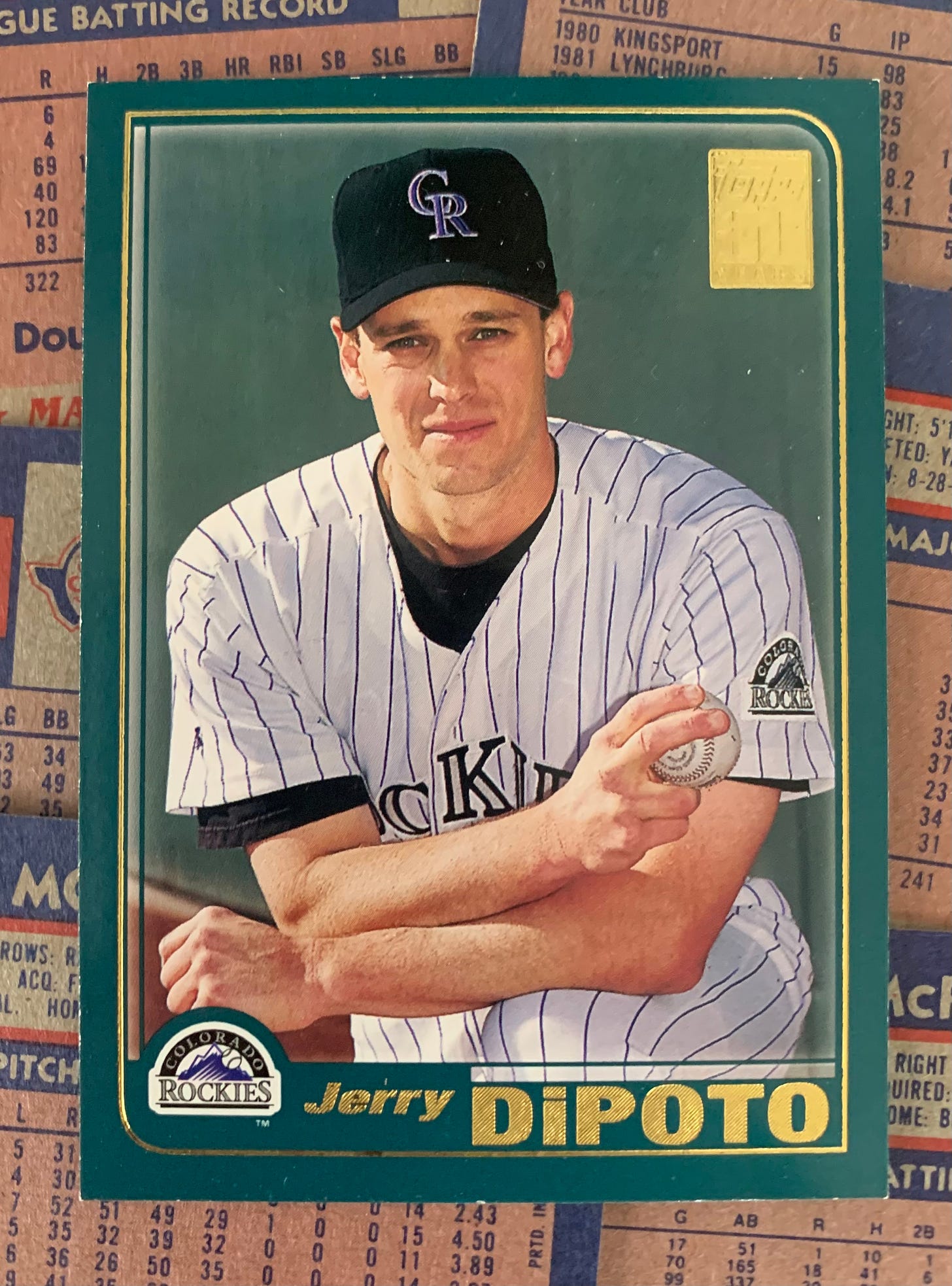

It was the first play from scrimmage. Avalanche defenseman Adam Foote lined up across from Rockies closer Jerry Dipoto.

Hut… hut… hike!

Dipoto took a step and a half, and -- BAM! -- next thing he knew he was on the pavement. A decleater, as the late great John Madden would have said.

Staring up at the Denver sky and gasping for breath after a forearm to the throat, Dipoto managed, “Adam, I thought we were friends.”

Since that story was told to me in 2011 by Dipoto, then a colleague of mine with the Diamondbacks, I’ve moved back and forth across the country, added a wife and two children to the roster, and hunkered down with the aforementioned family during a pandemic.

Let’s just say that I’ve learned to fact-check my memory when I can.

That’s why — shortly after the Colorado Avalanche captured this year’s Stanley Cup — I asked Dipoto if he’d retell the story of flag football with his neighborhood pals.

Graciously, he obliged.

Dipoto had been traded to the Rockies from the Mets prior to the 1997 season. Towards the end of his first year in Colorado, he and his wife bought a house in Littleton, a suburb of Denver.

The neighborhood, it seems, was Avalanche territory.

Across the street was Adam Foote, who was coming off his first All-Star season and clearly wanted to make sure that the baseball player felt welcomed.

Three doors down from the Dipotos lived Keith Jones, then a right winger with the Avs and now a commentator for the Flyers and rinkside reporter for the NHL on TNT.

Up the street, the man who wore the captain’s C for Colorado: future Hall of Famer Joe Sakic.

It’s a story in itself. On one block lived two athletes who, after their playing days ended, would both become general managers — Sakic of the Avalanche and Dipoto, first of the Angels and now the Mariners. Both have since been promoted to president within their respective organizations.

There was a vacancy for one more — and another future Hall of Famer at that.

Patrick Roy — the only three-time winner of the Conn Smythe Award as the playoff MVP — moved into the neighborhood. On the block directory, Dipoto fit like a Zamboni in the bullpen.

The neighborhood had filled up with Avalanche players.

Living next to Foote (diagonally from Dipoto) was a family with two teenage boys. In the late fall and winter evenings, Dipoto would venture out in the street to join the teens who were playing football.

He would prop up his baby son, Jonah, now a minor league pitcher with the Royals, securely on the lawn.

That Thanksgiving, a flag football game broke out. Socks, serving as flags, were tucked into belt loops and waist bands.

Foote, the rugged NHL defenseman, walked out of his front door to survey the scene. “It’s not my game,” he said, declining an invitation to participate.

Once a week during that baseball offseason, Dipoto would play flag football with the teenagers on the block. Eventually, Foote joined in.

One Sunday in the winter, Dipoto was watching football at home with teammates Curtis Leskanic and Jason Bates, along with Doug Henry, a former teammate from his time with the Mets.

The doorbell rang. It was the neighborhood kids wanting to play football.

“Can Jerry come play?” Dipoto jokes.

“I just went and banged on Footer’s door,” Dipoto says, not expecting that Jones and future Hall of Famer Peter Forsberg were also over.

Two households had been solicited to play football, and suddenly there was an MLB-vs.-NHL game with two kids as the team captains.

“Very quickly, we identified that the hockey players couldn’t run or throw particularly well,” Dipoto notes in what had to be one of his easiest scouting assignments.

Dipoto, QB of the team on this day, had a simple strategy: Go long and I’ll throw it up as soon as you clear the deep man.

The first to eight scores won. Dipoto remembers that after about eight passes, the game was over.

Taking the hockey players off the rink left them overmatched.

A week later, Foote called Dipoto looking for a flag football game. Doug Henry had left town, but Leskanic and Bates were still in the lineup.

“I lined up for the very first play of the game and Adam is covering me,” Dipoto remembers. Foote, in fact, is fairly close to the line of scrimmage.

“I take a step and a half, and he lays me out.” Staring up at the sky, socks dangling from his waist, Dipoto asked, “What the hell are you doing?”

“We don’t play that game anymore,” the defenseman with more than 1,500 NHL penalty minutes advised.

The hockey player had found a way to slow down the opponent.

Dipoto remembers “truly getting punished in the trenches” in that game, which the hockey players won, 8-7. “We needed to find a hot tub afterwards.”

With the series tied at one, there had to be a rubber match, right?

When it came time for another game, Foote explained to his neighbor: “I’ve thought about it. You’ve got a great arm and a lot of heart, but we choose not to.”

What?

“We won the last one, and we choose not to.”

Perhaps this decision reflects a classic hockey understanding, one that happily accepted games ending in ties before an American audience required shootouts to settle nightly deadlocks. Perhaps Foote tried something new before confirming for himself that football was not his game.

Before too long, Forsberg moved to a different part of town and Jones was traded to the Flyers. The rivalry had dissolved. Red Wings-Avalanche, this would not become.

“If you were just driving by and saw these guys with socks in their pants, you wouldn’t think, ‘That’s a future NHL Hall of Famer. That’s a Major League closer.’”

But it was.

“Something from a different era,” says Dipoto.