Welcome to Warning Track Power, a weekly newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

On the evening of December 31, 1972, a firehouse in Pittsburgh was vacated. Its doors, which first opened in 1896, were closing forever.

Almost simultaneously, about 1,700 miles to the south at Isla Verde International Airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico, the plane carrying Roberto Clemente and four others taxied down the runway on a flight that would end in catastrophe.

Baseball, often in moments of great triumph or defeat, makes us consider our own spirituality. How willing are we to acknowledge the presence of the baseball gods? Is any moment really fate, or is it simply a reasonable outcome over the course of nearly 25,000 games each decade?

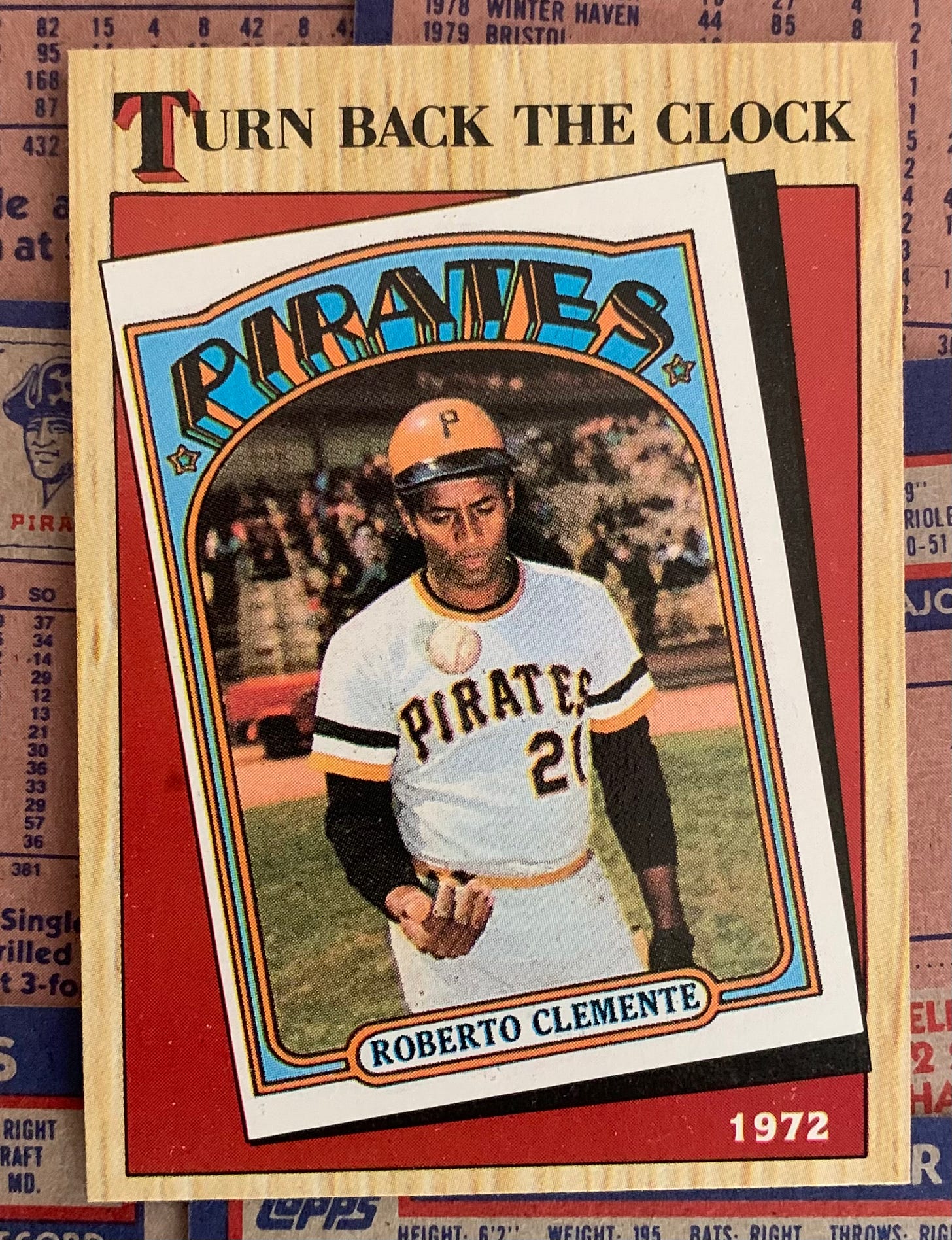

Such considerations are nothing new. But, 50 years after Clemente’s tragic death, the stories told and passed down — far away from the field — continue to shine a light on one of the game’s greatest humanitarians in a way that feels more than simply serendipitous.

The Westin Pittsburgh, where many if not all visiting teams stay, is a mile-long stroll from PNC Park. Cross the Roberto Clemente Bridge and behold a Major League field in a state of pre-game beauty ahead.

(I am fully aware that I’m not accounting for humidity, threat of rain, or severe downpours on getaway day. We celebrate sunny days here at WTP.)

Like the Allegheny River that runs under his bridge, Clemente’s legacy is forever flowing.

Before a visit to Pittsburgh while I was with the Diamondbacks, a colleague of mine — born and raised in the Steel City, a true Pittsburgher — suggested I visit the Clemente Museum.

Instead of the usual walk across the bridge to the stadium that day, my journey took me into Lawrenceville and as close to Clemente himself as possible.

In this revitalized Pittsburgh neighborhood, inside of historic Engine House 25, the Clemente Museum thrives.

There, also thriving, you will find Duane Rieder.

Commercial photographer, winemaker, and a generous vessel of all things Clemente, Rieder is an inadvertent collector turned executive director. His forthright and devout passion for the man, his family, the game of baseball, and the communities that intersect at the museum empower Rieder’s efforts to perpetuate Clemente’s impact.

To channel Roberto Clemente, visit Engine House 25, look around, and listen.

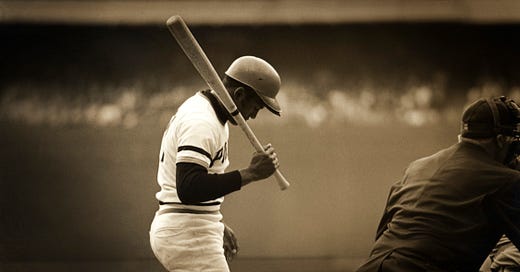

My father and I visited in 2012 and what we figured would be an hour-long visit lasted close to three. Rieder’s curation and narration were spellbinding. I often think of one of the museum’s signature pieces, an artfully displayed image of Clemente leaping for a ball in Spring Training, with clouds behind him shaped like angel wings.

The negatives of that photo were rescued from a dumpster after a local newspaper that had changed hands cleaned out its inventory. No print had ever been made of that decades-old shot.

An ambitious dumpster-diver discovered the negatives and knew where he could unload them. “A guy brings them here and sells them to me for a ton of money,” Rieder recalls. “Back then, my wife would’ve shot me dead in two minutes. Today, she’s like, ‘That was the smartest thing you ever did.’”

It’s as though there’s a magnetic force pulling Clemente artifacts to the museum.

“Those negatives, I look at those every day and go: How did that guy knock on this door?”

Rieder has similar stories of the provenance and journeys of other items, like the display of paperwork from Clemente’s career, pulled from a filing cabinet in a local dump. On the brink of disappearance, remnants resurface.

“I tell people every day: I’m the luckiest guy in the world… I get to talk about Roberto Clemente in this old firehouse.”

That old firehouse, which hasn’t functioned as a firehouse since 1972, presented the ideal workspace for Rieder. In advance of the 1994 All-Star Game, played at Three River Stadium, Rieder was commissioned to assemble a Clemente calendar. The assignment took him to Puerto Rico, where he visited the home of Vera Clemente, Roberto’s widow.

“She hugs me,” Rieder says, “and I’m not a hugger.” It’s the moment where his relationship with the family begins.

“She’s hugging me, and I just feel this warmth… she didn’t even know me; she only knew me as the photographer.”

In the backdrop of that warm embrace was a house in disrepair. Hurricanes had flooded the house. Clemente’s trophies were tarnished. Photos were ruined.

Back in the states, Rieder leveraged his professional photography connections and know-how. He returned to Vera with photos of her husband that she had never seen before. Shortly thereafter, Vera named Rieder the official Clemente family archivist.

The museum wasn’t yet a consideration, but Rieder needed a home for his photography business. The firehouse offered outstanding studio space. He went for it in Lawrenceville and became somewhat of a pioneer in the downtrodden neighborhood.

Today, it’s a building full of memories, mysticism, and history.

Only two players in the history of the game have ever had the mandatory five-year waiting period for Hall of Fame election waived: Lou Gehrig and Clemente.

Well, during the 1927 World Series, Gehrig visited a former minor-league teammate who had become a firefighter in Pittsburgh. That firefighter, of course, was a part of Engine House 25. Gehrig spent the night at the station — the station that is now home to the Clemente Museum.

While speaking with Rieder, I was struck by the massive additions and growth the museum has enjoyed over the past 10 years. Everyday, Rieder says, the museum is acquiring a new photograph or piece of memorabilia. (Tours are available by appointment only and are especially popular during baseball season.)

New stories continue to emerge as well. Former Pirates pitcher and broadcaster Steve Blass participated in an event at the museum this past New Year’s Eve. At some point during the evening, Blass mentioned that — after Clemente’s death — President Richard Nixon had HUD, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, write a check to Vera Clemente to help her launch Sports City.

Sports City was Clemente’s vision, a center in Puerto Rico where children could play and learn.

Rieder had known the Nixon himself had cut a $1,000 check to support the program, but it wasn’t until a couple weeks ago that he learned of greater government involvement.

“I know stories from 50-100 people that really knew Roberto. They came here as part of their bucket list to tell me one story before they died,” Rieder says. Those stories live throughout the building, on the walls and in the air.

Meanwhile, in the basement of the building, Rieder houses Engine House Twenty Five Wines. He sources grapes from a number of regions, including Napa, Sonoma, and Lodi. How did he get his start in winemaking and what do the Pirates have to do with it? I think we’re better off saving that story for another week.

After all, this year will mark the 50th anniversary of Clemente’s induction in Cooperstown. We’ll need something to toast with.

For more information about the Clemente Museum, click here.

Fantastic read on Clemente.. I had no idea the museum had all that history behind the story of the location. Great stuff!