Welcome to Warning Track Power, an independent newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

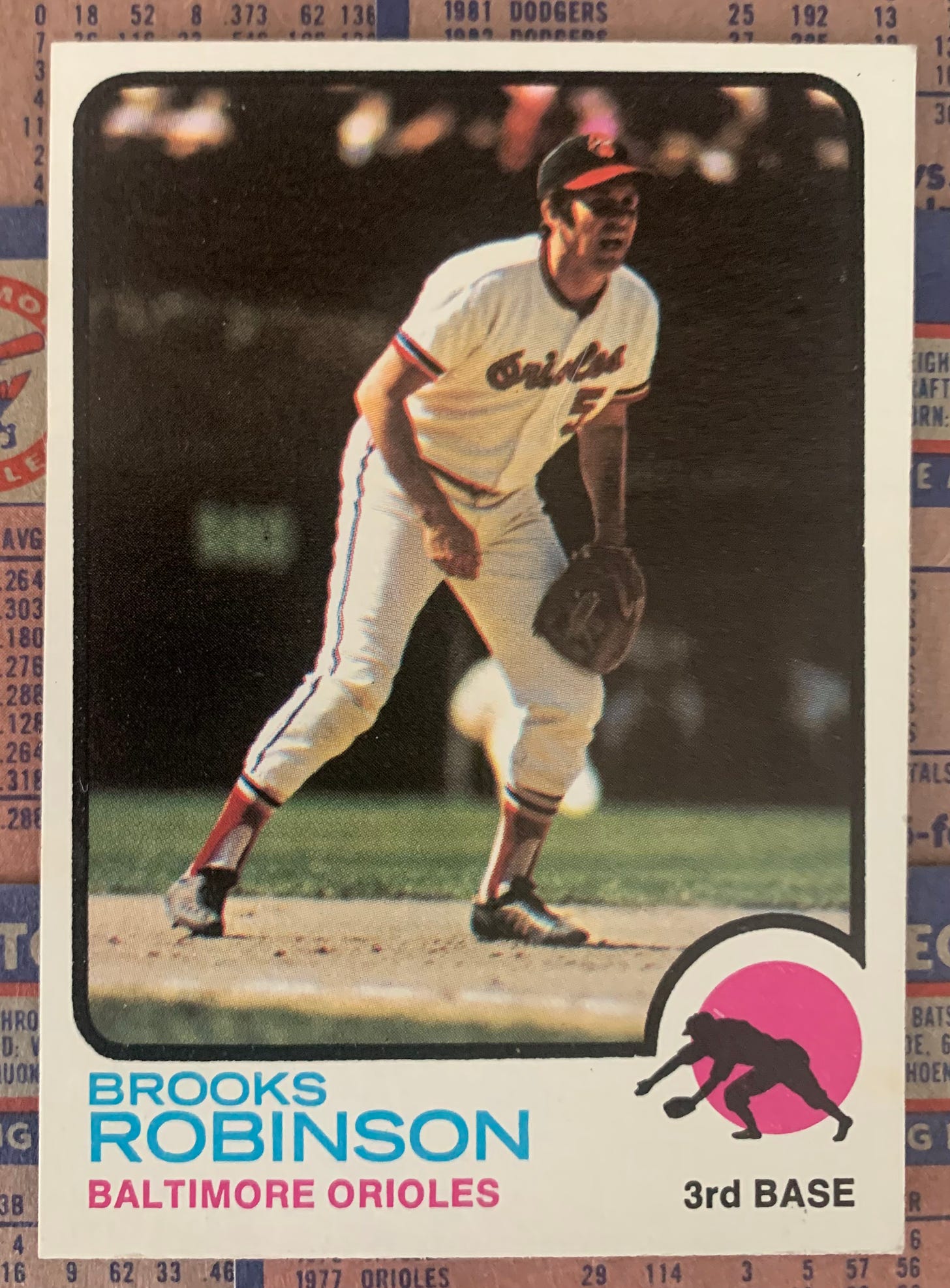

When I learned that Brooks Robinson had passed away on Tuesday, I immediately thought about my family. Both of my grandfathers adored the man. They told stories of glove work, athleticism, and World Series heroics; they saw it as both my birthright and responsibility to appreciate and understand what Brooksie had accomplished in his career and done for Baltimore.

I thought of my parents and my aunts, all of whom were around the right ages to idolize their home team’s third baseman. Every Oriole and every Major Leaguer at the hot corner was measured — unfairly, perhaps — against Brooks. He was the pride of Baltimore.

After his playing days, any Brooks sighting or encounter became major family news. It was a brush with greatness, an accessible greatness. The man was so kind, so available, that he could be The Greatest Third Baseman of All Time and also one of them. He was the perfect hero.

I thought of Jim Marshall, his roommate in 1958. Both Marshall and Robinson were looking to establish themselves as big leaguers that season. The 21-year-old Robinson had appeared in 71 games for Baltimore’s big league team over the previous three seasons. His defensive prowess was already unquestioned, but his bat was a pronounced weakness.

Marshall, six years Robinson’s elder, had spent the previous season in the Pacific Coast League, playing for the Orioles’ affiliate in Vancouver. He hit 30 home runs and drove in 102. His Major League debut seemed imminent.

Marshall and Robinson rented the upstairs of a private Baltimore home that was close to Memorial Stadium. Earlier this week, Marshall (who was featured in this space last offseason) was kind enough to share a story and some thoughts about his old roommate:

“The granddaughter of the people who owned the home where we stayed, she really liked Brooks. And she worked for the telephone company, so anytime we wanted to make a long-distance call, she took care of it for us.”

Marshall chuckles at the memory. “And I give Brooks all the credit for that… in those days, that meant a lot: Your family’s in California, and you’re in Baltimore.”

He spoke generally about the daily “off-the-cuff” things that two ballplayers would have fun doing together. They were relatable everyday interactions that happened to feature one soon-to-be extraordinary third baseman. As Marshall recalls, “You have fun and you go onto the next thing.”

Marshall remembers his friend’s positive nature: “Nothing could get him down. He always smiling and always giving his best.” Perhaps that attitude is part of what enabled Robinson to develop at the plate.

“Everybody talks about his fielding, but I talk about his hitting. He improved it so much,” Marshall says with a sense of wonder that hasn’t faded over 65 years. “He was a terrible hitter, terrible hitter! And [Orioles manager] Paul Richards stuck with him. I don’t know if it was [hitting coach] Eddie Robinson who helped him or if he just helped himself, but in about three years… just look at the records. It’s something to really be proud of.”

We all know what Robinson looked like over the course of 16 consecutive Gold Glove seasons that included 15 straight All-Star games. His old roommate’s amazement at Robinson’s offensive transformation reminds us of the desire, fortitude, and makeup the young player possessed.

“He was just a pleasure to be around,” Marshall says. “He and I had a lot of fun. I hate to see him go.”

WTP offers free and paid subscriptions. Sign up now and never miss a word.

Beautiful story, Ryan. Great to get the perspective of not only you but Marshall, too.

What a lovely tribute to such a special guy!