Unwritten Rules & Bonus Pools

Players are about to get more than they collectively bargained for

Welcome to Warning Track Power, a weekly newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

With two outs in the top of the ninth and his team leading by six, Thairo Estrada took off towards second base as the pitch was delivered. Brandon Crawford put the ball in play, blooping a single into shallow left-center field. Running all the way, Estrada tried to score. He was thrown out by Nationals shortstop Alcides Escobar, who proceeded to share his displeasure over Estrada’s overzealous baserunning with the entire stadium.

If the stolen base attempt violated one unwritten rule, the decision to send the runner broke another.

These unwritten rules sure are written about a lot. Well, maybe they’ve finally met their match.

The Pre-Arbitration Performance Bonus Program, which sounds like something the Wilpons once invested in, represents an emerging market in player compensation.

This new feature in the Collective Bargaining Agreement sets aside $50 million annually for players yet to qualify for salary arbitration. It also excludes players signed as foreign professionals, like Cubs rookie Seiya Suzuki, and “extended free agents,” which I interpret to cover players like Fernando Tatis Jr. and Wander Franco, both of whom signed long-term deals before reaching arbitration or free agency.

There are fixed bonus amounts for any qualifying player who finishes in the top five in MVP or Cy Young voting or in the top two of Rookie of the Year voting. There’s also a bonus if a qualifying player lands on the All-MLB Team, an honor very similar to the NFL’s All-Pro Team. Honestly, I didn’t even know such a distinction existed prior to researching these bonuses. The All-MLB Team began in 2019.

If this system had been in place last year, during the 2021 season, there would have been $9,250,000 distributed to those award finalists. NL Cy Young Award winner Corbin Burnes would have tripped over the footnote stating that a player can only receive a single bonus. He would have taken home $2.5 million for the Cy Young hardware and not received the $1 million bonus for making the All-MLB First Team. Back into the pot it goes!

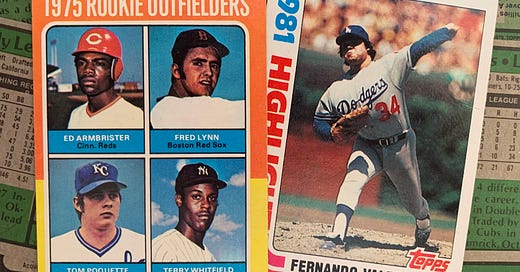

Somewhere, Fred Lynn and Fernando Valenzuela are shuddering. Their historic Rookie of the Year campaigns would have been rendered moot by this system. Lynn also won MVP honors in his rookie season of 1975, and Valenzuela won the Cy Young in 1981, his first year. Of course, either of those guys would have been quite content with a $2.5 million bonus check.

The remaining pool money — in the hypothetical case of last season: $40,750,000 — is allocated among the top 100 eligible players “according to a statistical formula (modeled after WAR) to be developed by a Joint Committee comprised of representatives from the Commissioner’s Office and the Players Association” no later than July 1, according to a memo from the Commissioner’s Office.

Why do I have a feeling that some folks from MLB and the Union will be deep in Excel files on June 30?

What that formula will be is anyone’s guess. Even the most commonly used WAR metrics vary; Baseball-Reference, Baseball Prospectus, and Fangraphs each use different formulas that, for some players, yield drastically different results.

Also, how will the money be dispersed among the 100 players? We should hope for a sliding scale or threshold-based allocations. Will it look like prize money distribution for a PGA Tour event?

Regardless, let’s appreciate that 100 players who are otherwise making the Major League minimum ($700,000 in 2022) will get a little something, you know, for the effort. On average each bonus should be about $400,000.

Going 100 deep in a pool of pre-arbitration players opens this contest up to anyone in an everyday role. But the number of eligible players is larger than you may think.

Warning Track Power is a reader-supported venture. Free and paid versions are available. The best way to support WTP is by taking out a paid subscription.

According to an article written by Travis Sawchuk around the time of the lockout, of all players to appear in a game in 2019, 63.2% of them had less than three years of service time. That group of about 950 total players essentially represents the beneficiaries of this new windfall.

Now we’ve reached the point where the unwritten rules meet the $50 million bonus pool.

WAR is a deeply singular metric in an otherwise team sport. It’s also naive to believe that a proper evaluation can include only one metric, but that’s not today’s problem.

More importantly for us right now, WAR doesn’t discriminate against a garbage-time home run off of a position player. This bonus program has, in a way, eliminated meaningless innings and unwritten rules.

How transparent will the relevant parties be with the formula and the standings? Real-time updates would generate additional interest in games, teams, and specific players, but it might also turn some players into their own daily fantasy team of one.

Of course, I can see it creating gambling and sponsorship opportunities that the league would enthusiastically welcome.

NFL teammates are notorious for cooperating with players who need a certain number of yards or receptions to trigger bonuses in the final week of the regular season. Does this program have that kind of potential?

Regardless, there’s a balance between eligible players understanding what’s at stake financially and what remains of the unwritten rules. This bonus program has introduced a dynamic that incentivizes a percentage of players to accumulate statistics regardless of the score or situation. The idea of playing to the scoreboard is lost.

Giants infielder Mauricio Dubon bunted for a single in the sixth inning of a game against the Padres when San Francisco was leading, 11-2. The Padres were not happy.

As mentioned earlier, Thairo Estrada ran the bases aggressively in the ninth inning — unusual given the generally accepted conventions.

In both instances, manager Gabe Kapler explained that his team is looking beyond the game at hand and considering how, for instance, getting deeper into an opponent’s bullpen could impact the next day’s game.

Conveniently enough, both Dubon and Estrada are at pre-arbitration levels of service time. Another base hit, an extra stolen base, or one more run scored positively impacts their WAR. And now, their WAR can positively impact their bank accounts.

Did we already forget that just seven weeks ago, players were still locked out by owners? As the two sides negotiated over hundreds of millions of dollars, the Union — with an executive subcommittee that includes the incredibly well compensated Max Scherzer, Francisco Lindor, Marcus Semien, and Gerrit Cole — pushed hard to establish a program that rewards players making at or near league minimum.

Congrats, everyone! Now that the bonus pool is reality, how does it change the conversation that Padres first baseman Eric Hosmer, who’s signed to an eight-year, $144 million contract, has with Dubon, who is making $715,000 this year assuming he remains in the big leagues? Both players are governed by the same CBA, and all agents are part of the same union.

Even if the Giants players are motivated by an overarching team philosophy, the biproduct should still help them climb the WAR leaderboard.

Uncle Max, Uncle Francisco, Uncle Marcus, and Uncle Gerrit have fought for $50 million to be allocated to its youngest stars. How will they handle the side effects of the system they created?

The season is underway, and WTP is offering free and paid versions. Thank you to all who have supported this newsletter with a paid subscription. Subscribe now and never miss a single edition.