Band People Win The Pennant

Just out of the spotlight, keyboardists and platoon players grind it out

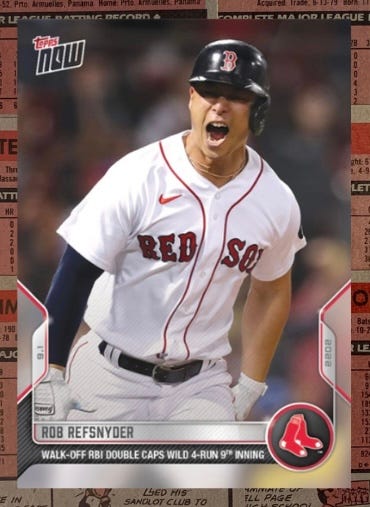

Rob Refsnyder went 4-for-4 last Monday. He hit two home runs, drove in five, and sandwiched a walk in between all the damage.

Nine seasons into his Major League career, Refsnyder has played for the Yankees, the Blue Jays, the Rays, the Rangers, the Twins, and now the Red Sox — six teams in all, including every team in the AL East except for the Orioles, the team he vanquished with his most recent offensive outburst.

The former fifth-round draft pick out of the University of Arizona has settled down — on a platoon basis, of course — in Boston’s outfield. In his earlier days, he moved around the field more regularly, logging innings at first, second, and third base in addition to all three spots on the grass. Refsnyder’s career is that of the versatile journeyman. Let’s not mistake versatility, however, with security; case in point: amidst a career year, he floated the idea of retirement. In 2024, he’s established career highs in games played, plate appearances, homers, and RBIs.

The job of a role player, seldom guaranteed beyond the current season.

Baseball’s bench players aren’t too different from film’s character actors. In music, they’re sidemen and supporting musicians.

In his new book, Band People: Life and Work in Popular Music, Franz Nicolay explores the challenges, tensions and adventures of rock and roll’s supporting cast. Nicolay, who some of you know already as the keyboardist for The Hold Steady, appreciates the impact that role players and unheralded coaches can have on a team and fan base.

Baseball’s band people

“I guess the equivalent might be the kind of organizational people,” says Nicolay, “like a minor league roving catching instructor who’s not gonna get much attention but is really gonna shape the way a team at the Major League level looks in terms of… ‘What kind of framing are you prioritizing? What kind of game-calling strategies are you prioritizing?’ This is going to be a really crucial guy in an organization.” I can’t help but smile at how easily Nicolay toggles between music and baseball, or at how happy he seems to continue to talk ball.

“The other way of thinking about it is the framing that I use of talking about character actors: What’s the difference between, like, a Jeff Goldblum, who shows up in a movie and he’s just being himself — but that himself is so compelling that you’re going to remember it — versus the kind of character like Mark Rylance, or somebody who can disappear into a role or pride themselves in disappearing into a role. I think you have people like that, even at the big league level.” Baseball’s Goldblum might surface as Tommy Pham or Jonny Gomes. Meanwhile, Alex Cobb and Josh Bell don’t seem to mind disappearing into a role.

Nicolay continues: “These guys who will have a 10-year career… off the bench but are really crucial for specific situations; somebody like — on the Red Sox this year — Rob Refsnyder, who mashes lefties. He’s been a mentor for the younger guys.” Championship teams usually carry this type of player on their roster.

“I’ll never forget Phil Plantier from… the ’91 Red Sox having an incredible September, and that was, that was the high point of his career. [He hit .320 and slugged .619 in that month, clubbing eight homers.] But, especially as a young person, and especially as a young person who — now I’m getting more about baseball than I am about Band People, I think — but if you’re a young person who’s into baseball, but you know that you don’t have… the skills [to go very far], you know you can really attach yourself emotionally to, like, a utility infielder. For me, it was Marty Barrett. It’s like, I’m obviously not the best player on the team, but I got a long way on baseball smarts, and you can identify with that.”

It looks like I, too, have gotten more into baseball than Band People. But sharing these stories is also my way of recommending the book, which came together after about 100 hours of interviews Nicolay conducted between 2014-2016, when he’d stepped away from performing. His research, eloquence, and subject-matter expertise create a strong foundation for lively insights shared by many musicians. Nicolay’s authentic exploration of humanity makes Band People a captivating read even for those without an encyclopedic knowledge of modern music.

One of my favorite lines of the book’s introduction delves into an issue that has certainly cost more than one baseball coach his job:

We are comfortable with the mythos of creativity unbound, but what does creativity bound look like—creativity within parameters, and restraints (if one choose to be creative within those bounds at all)?

At a certain point, both band people and, say, minor league coaches must surrender opinions and yield to organizational philosophies. Those parameters aren’t always easy to identify or respect, though. Disagreements over territorial boundaries have undone more than one band. The universality of that paradigm makes the stories in Band People eminently relatable.

Songwriting credits cause some of the tensions in bands, as they determine royalties. I picture Refsnyder sitting on the van with the bass player and the drummer; they’re the part of the band most likely to stare into an empty mailbox when royalty checks arrive for the lead singer and guitarist.

Contemplating retirement during a break-out season sounds crazy until you consider Refsnyder’s journey. He’s been optioned to the minors nine times, designated for assignment three times, traded three times, claimed off waivers once and released once. He spent the entire 2019 campaign in the minor leagues. A sort of wariness sets in that’s not uncommon to the pages of Band People.

Refsnyder has shared locker rooms with Mark Teixeira, CC Sabathia, Aaron Judge, Matt Holliday, and Blake Snell. He’s been good enough, been told he’s not quite good enough, and has been asked repeatedly to prove he belongs. Now that he finally may have earned security, does he have enough passion and energy remaining to enjoy it?

Musicians’ makeup

Plenty of teams will tolerate a player’s questionable habits and behavior if the on-field performance is good enough. “That’s not necessarily the case in the music world,” Nicolay says. Band People spends time focused on the importance of being “a good hang.” It’s baseball’s equivalent of intangibles and being a good teammate.

“You’re spending one hour on stage and 23 hours off stage,” he says. (I feel the need to note that The Hold Steady routinely gives its audiences two-plus hours of music, but the point is still taken.) “You want someone in your group who’s going to make that 23 hours as pleasant as possible.”

The book offers honest and unprejudiced access to the realities of touring musicians’ lives. On more than one occasion, I wondered if Band People is, in its own way, the Moneyball of music. Might Nicolay’s journey into a specific corner of the music world inspire others like Michael Lewis’ bestseller inspired me and so many of my peers?

Band People is available for purchase most places you find books, like here on Amazon or from University of Texas Press. For more from Nicolay, check out his recently created substack — named in honor of a Warren Zevon song — where he shares, among other stories, full versions of some of the interviews from Band People.

Speaking of bonus material, I have a lot more from an enjoyable 30-minute conversation with Nicolay. We spoke a couple weeks ago in the lead-up to his book’s release, and I plan on sharing some additional stories that I think baseball fans and music fans will appreciate.

WTP offers free and paid subscriptions. Sign up now and never miss a word.

interesting piece...I like how you seamlessly merged these two different worlds.