Welcome to Warning Track Power, a weekly newsletter of baseball stories and analysis grounded in front office and scouting experiences and the personalities encountered along the way.

If you don’t already subscribe (for free), please consider doing so today. And if you enjoy WTP, go ahead and share it.

Legend has it that during the 1981 strike, some of the Orioles would practice on the baseball field at Gilman School in Baltimore. Perhaps because I first heard this story while a student there, I never questioned its validity or sought further details. It was a recess rumor.

As a second grader at Gilman and with the O’s on the verge of their first and only World Series of my lifetime — the most prodigious part of the account felt undeniably true.

Eddie Murray, they said, hit a ball to the Harris Terrace — the landing above the permanent steps that served as bleachers for fans of the home team at football games. That’s a poke.

Once the ball traveled out of right field proper (there was no fence), it then had to travel the width of the gridiron and up a significant flight of steps.

Some said 500 feet. Others said 550. I had neither reason nor desire to challenge the tale.

The varsity field has since moved, but the mojo remains.

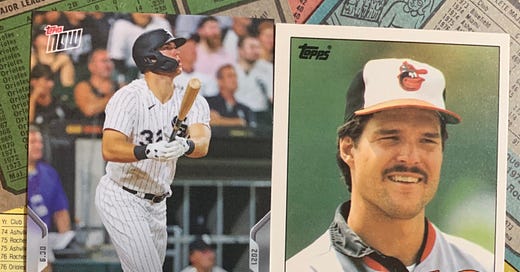

When Gavin Sheets dug in against Kenta Maeda of the Twins on June 29, he became the first Gilman grad to appear in the big leagues.

His father, Larry, played for the Orioles from 1984-1989, and he’s been the head coach of Gilman’s varsity baseball team since 2010.

At that point, there was already another familiar last name on campus.

“When I took the job at Gilman, one of the first people I called was Cal,” he said. Really, do you need me to provide the last name?

Ryan Ripken, Cal’s son, was already at Gilman, making the Ironman’s decision to join the coaching staff an easy one.

This pedigree is relevant because as I’ve watched many of Gavin’s plate appearances, I have been struck — thoroughly impressed — by his plate discipline and pitch recognition.

American League pitchers have thrown fastballs just a touch over 50% of the time this season. Gavin, who’s listed at 6’5, 230 lbs., has seen fastballs at a lesser rate — about 45%. He’s had the kitchen sink thrown at him since his debut, with many pitchers going changeup or curveball heavy on him. Long gone are the days that a pitcher attacks a rookie with fastballs until the batter proves he can handle them.

The younger Sheets has a stillness in the box befitting of a veteran player who has honed his approach over hundreds of big league at-bats and thousands of hours in the cage and film room. That’s not to say he doesn’t swing and miss, but his K-rate is a few points below league average, and his slugging percentage (.483 as of end of play on Wednesday) is well above the AL average of .410.

If we knew where that maturity came from, someone would have already tapped and bottled it, then sold it. For Sheets, I believe it’s a combination of innate talent, bloodlines, high baseball IQ, dedication in the proper areas, and exposure to the right people and the ability to distill information for himself. He seems to know what kind of hitter he is, and he doesn’t try to be someone else. As a 25-year-old rookie on a first-place team of stars — and young stars at that — it’s requires all of that to earn a spot in the lineup.

The pairing of Gavin with Hall of Fame manager Tony La Russa also benefits the young player. “He’s old school,” Larry says of La Russa, “and Gavin was certainly brought up old school baseball wise.”

Larry was managed by Hall of Famers Earl Weaver, Frank Robinson, and Sparky Anderson during his career. It’s uncanny that his son plays for a manager who has already been enshrined in Cooperstown and was managing while Larry was playing.

Father and son were also both selected in the second round of the MLB Draft. Larry was taken in 1978, 29th overall, a pick that would still be in the first round today. The O’s had a second pick in the second round that year, too, and with that 48th overall pick, they selected a kid from Aberdeen, Maryland, who would go onto play in 2,632 consecutive games (and serve as an assistant coach at Gilman).

Now here comes Gavin, whom the White Sox selected 49th overall in 2017 out of Wake Forest.

Clips of his first six career homers, which can be found right here, show why pitchers turn to off-speed against him. He can hammer fastballs in, and he can drive high heat the other way. He’s also been known to punish a changeup, and that’s where his preparation and instincts serve him.

The pandemic put an end to Gavin’s minor league season in 2020, but he was working out with Cal and Ryan Ripken regularly.

“He’s had a chance to sit down with Eddie [Murray] and talk to him about hitting,” says Larry, adding that his son has had access to many of his former teammates. “I’d rather have him talk to the guys I played with because I trust those guys.”

What I would call Gavin’s signature moment in his young career so far occurred in Game 2 of a doubleheader against the Twins on July 19.

Two-time All-Star José Berrios, who was traded to the Blue Jays last week, struck out Sheets in his first two at-bats of the seven-inning game. Sheets saw 11 pitches over that span — only one fastball.

Trailing by one run in the bottom of the seventh, Sheets came to the plate with two on and nobody out. Berrios’ first pitch was a fastball, taken for a ball. The next pitch was a curveball that almost hit Sheets. This is where the at-bat gets good.

Refusing to give in, Berrios throws a 2-0 changeup that Sheets spits on. Given the situation, it was a perfect pitch: A fastball count against a rookie who has a chance to be the hero. Berrios was playing to what he expected would be an overexcited batter whose adrenaline would have him coming out of his shoes at the pitch.

But Gavin showed the ability to slow things down and keep a slow heartbeat. So many batters would have swung at the change — it was a very good pitch! — and flipped the dynamic of the at-bat. Not tonight, José.

With a 3-0 count, Gavin took a fastball running away from him for a strike.

Still behind in the count and having only shown Gavin three fastballs all night, Berrios tried to double up on the heater and sneak one by him. As the replay shows, Berrios threw the pitch exactly where he wanted it — 96 MPH down and in… right into Gavin’s nitro zone.

After being served soft stuff all night long, the ability to turn on plus velocity and deposit it into the right field bleachers is impressive. You can see the final three pitches of the battle here.

As a proud alumnus, it’s been fun to adopt a new favorite player (sorry, Shohei) and observe the development of a rookie from afar. Gilman has had some outstanding teams and players over the years, so it’s not a huge surprise to me that a Greyhound is finally in The Show.

Want a surprise? That’s when our next big leaguer enters…

I never saw Stephen Ridings pitch in person while he was at Haverford College, and I was smart enough not to return for an alumni game when he was still a student.

It was a big enough deal when the Cubs selected him in the eighth round of the 2016 Draft and he left campus after his junior year to pursue professional baseball.

On Tuesday at Yankee Stadium, when his first pitch registered 101 MPH, he cemented himself as Haverford’s first Major Leaguer since Bill Lindsey, who hit .242 over 19 games with the Cleveland Naps in 1911. (Lindsey, it turns out, accumulated degrees from a few institutions, so I’m content to call Ridings the first ever out of Haverford.) With a strikeout of DJ Stewart, Ridings was in the books forever.

I scouted Ridings during the summer of 2017 when he was still with the Cubs. He was less than a year removed from Tommy John surgery and was already on the mound in live games in the Arizona Summer League.

His fastball was around 88-89, and he had no feel for his breaking ball. It was impossible for me to file a complete report because I knew most pitchers in his situation wouldn’t even be on the mound at that point, and I also had known of his fastball topping out at 98 during his junior year at Haverford. Simply, this wasn’t the same guy the Cubs had drafted.

I asked Nat Ballenberg, who was Ridings’ pitching coach at Haverford and is now the special projects pitching coordinator for the Minnesota Twins, to help me fill in the blanks. How did this kid from Commack, NY — known to me only as a Long Island hamlet, home to one woman who made a fantastic choice in a husband — go from a D3 program to Yankee Stadium?

Turns out that Ballenberg was recently reminiscing with some of Ridings’ former teammates, and he shared this:

The thing about Steve as a freshman is that he was bad. Really bad. The heater was 79-86 and all over the place. He looked like a Gumby doll out there. As one teammate said: “I knew I could bunt for a hit against him, but I didn't want to get in the box because he hit me every time.”

That's a pretty accurate description of 17-year-old Stephen Ridings. It’s an only slightly less accurate description of 19-year-old Stephen Ridings. But the cool thing about Steve is that he started to work.

He always claimed he wanted to be great, but something started to click the summer after his sophomore year. I remember him telling me about a conversation he had with his longtime coach from back home. Steve realized that he could claim he wanted to be great all day, but until the work ethic matched the words he’d remain the same kid, pitching occasionally out of the Haverford bullpen.

So he shows up for the fall of his junior year and starts hitting 90. And then 91. And then 92.

And that hint of success sent him into overdrive. He worked his ass off. He got stronger, worked on his delivery, and hit 94 in the Fieldhouse in February. And then 96.

He dominated that year, touching 98 against Hopkins, before getting drafted in the 8th round.

As Tom Verducci’s book The Cubs Way details, Ridings mechanics and frame (he’s now 6’8) put him in elite company in terms of extension at his release point. He let go of the ball seven feet in front of the rubber, greatly limiting the hitter’s reaction time.

Ballenberg continued:

But then came Tommy John, and an awful year in Arizona where he struggled to throw strikes. Another rough year followed, and a delayed start in ’19 kept him in rookie ball. COVID hit in 2020 and he got released, but that’s where the fun begins again.

He spent the entire lost year in Jupiter, training at CSP [Cressey Sports Performance]. He worked his ass off. Things started to click. He touched 101 in front of a Yankees scout. And now the skinny kid throwing 80 is in the Big Leagues sitting 100.

It’s a wonderful story about one of Ballenberg’s original “special projects.”

As Ridings mowed down Orioles hitters and lit up the radar gun, the texts to and from former college teammates rolled in. He struck out the first two hitters and brought the Yankee Stadium crowd to its feet. After surrendering a double, he punched out Pat Valaika on a breaking ball and his night was done. He had put up a zero.

Will you humor me for one more paragraph?

One week from today, on August 12, the Yankees play the White Sox in Dyersville, Iowa, at the Field of Dreams. How much magic in the moonlight will it take to put Gavin Sheets in the box against Stephen Ridings for one at bat?

Thank you for reading Warning Track Power. Subscribe now to have WTP delivered to your inbox every Thursday. Baseball is the best. Go Greyhounds! Go Squirrels!

One of my favorite pieces of yours to date. Possibly my favorite sentence in this was “The thing about Steve as a freshman is that he was bad. Really bad.” One thing Ridings and I had in common as Squirrels!