Earl Weaver Demands Your Attention

Every so often, it feels like a book was written just for me. As faithful readers of Warning Track Power, I’ve got great news: This book was written just for you, too.

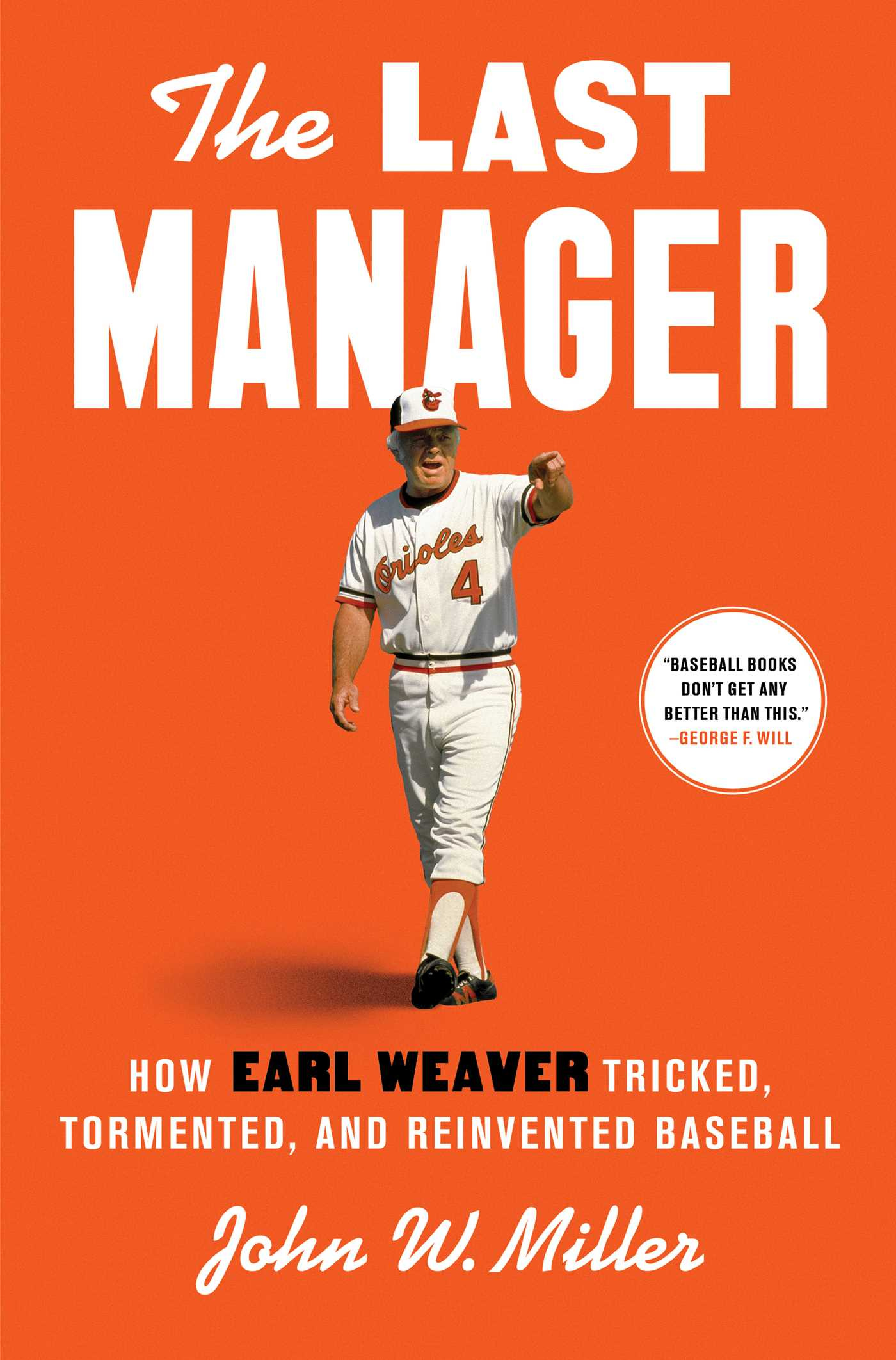

In The Last Manager: How Earl Weaver Tricked, Tormented, and Reinvented Baseball, widely available today, John W. Miller examines the legacy of the Hall of Fame manager, from his scrappy childhood in Depression-era St. Louis, alongside the trains and buses through the minor leagues, and finally as one of the main attractions in the Orioles dugout.

As an O’s fan who fell in love with the game in the time of Weaver, the stories took me back to childhood while educating me about a man I thought I knew. Regardless of rooting interests, Miller’s research and lively style bring to life a baseball pioneer whose body of work demands recognition in a game recently revolutionized by data.

I spoke to Miller a couple weeks ago, and was grateful to revisit some of my favorite parts of the book.

“I’ve thought about this story my whole life,” says Miller, who was born around the time of Eddie Murray’s Rookie of the Year campaign. “When I was a little boy living in Brussels, somebody gave me a copy of Earl Weaver’s memoir, It’s What You Learn After You Know It All That Counts. And, as a 10-year-old, I loved that book, and so I’ve been thinking about the story my whole life, and I think that’s why the book is what it is… it’s been marinating for decades.”

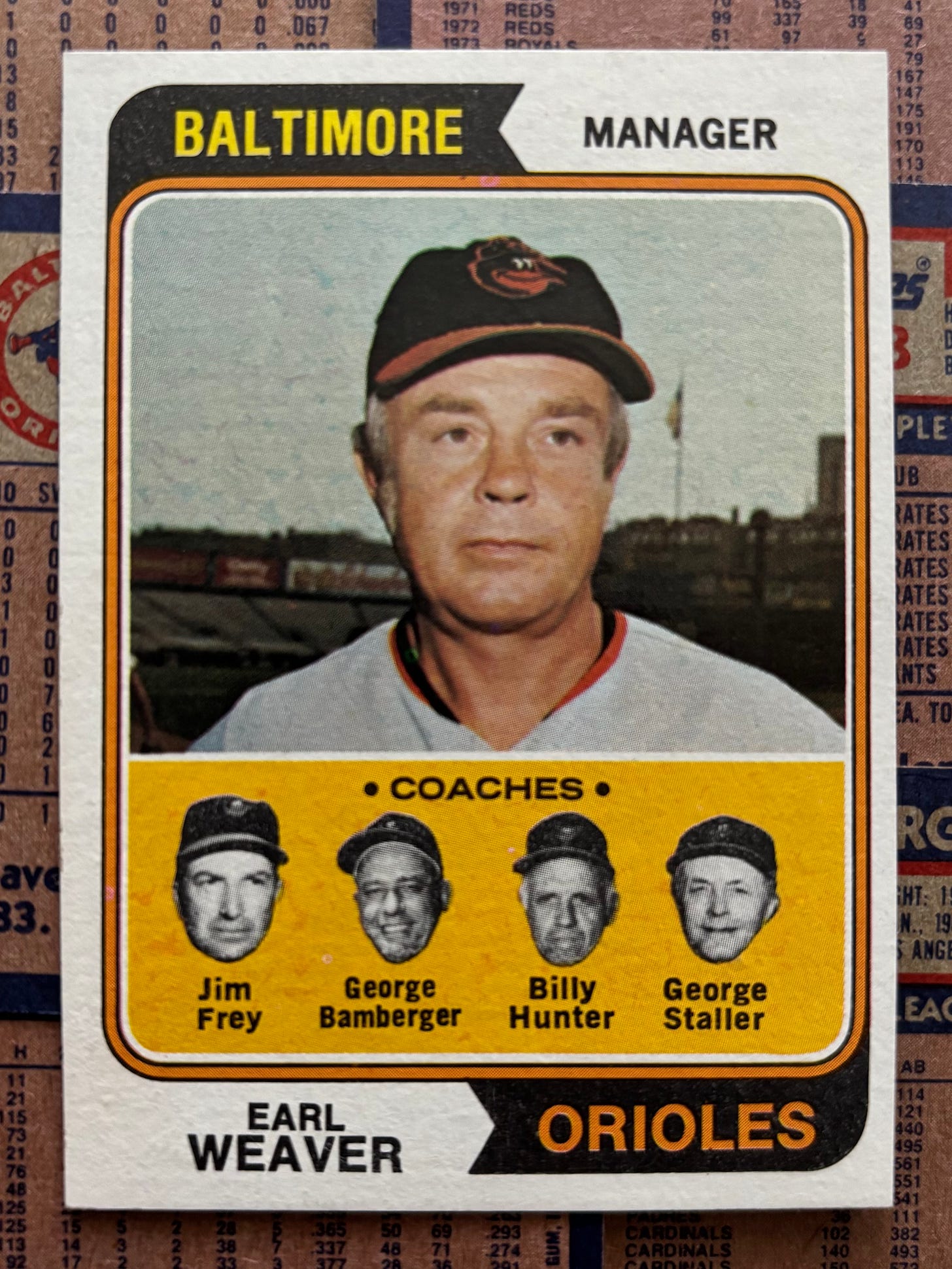

In an era before statheads battled the scouts, before subjective ran into objective, before a manager’s moves were scripted, there was Weaver. There was the child, obsessed with baseball and adoring his uncle, a local bookie. There was the young man — still just a kid, really — overwhelmed by 500 other minor leaguers at a Cardinals minor-league camp in Albany, Georgia. Then there was the manager, the imminently quotable entertainer who pushed all the right buttons to secure the highest winning percentage of any manager with at least 1,000 victories from the time he took his spot in the Baltimore dugout midway through the 1968 season.

Miller poured himself into the research, connecting with members of Weaver’s family, visiting the significant landmarks and neighborhoods from the manager’s life, digging deep into newspaper articles, books, and recordings, and interviewing many of the players who knew Weaver as their manager.

Who first brought the radar gun into baseball? Who was dubbed “Mr. Computer” by the press during the 1979 World Series?

Weaver studied probabilities and statistics before the Moneyball generation was born. His decisions were guided by the numbers, yet he was introspective enough to allow his beliefs to evolve over 17 years as a big league manager. He was an innovator whose combustable temper sometimes obscured his creativity.

The Earl of Baltimore mainlined stats into the game. Long before sacrifice bunts fell out of fashion earlier this century, Weaver was preaching the importance of every out. He reminded us that you only got 27. But who listened?

Before any of this, though, Weaver was an undersized second baseman playing in the Cardinals system.

During Spring Training of 1952, the 21-year-old Weaver outplayed the competition for a backup infield spot on the Cards’ big league roster. The only trouble: His competition was also the manager, and Eddie Stanky wasn’t ready to hang up his spikes. Until reading this book, I would have never known that Weaver had come so close to realizing his boyhood dreams of playing in the Major Leagues. Miller, who wrote the manager’s obituary for the Wall Street Journal (his employer at the time of Weaver’s passing in 2013), hadn’t known the extent of Weaver’s playing career either.

“It… explains a lot of his psychology of insecurity and vulnerability to the institution — to Major League Baseball — and the Major League Baseball players who are taller, more handsome and more accomplished than he was. It’s easier for him to deflect the criticism by saying, ‘Oh yeah, I wasn’t very good,’ then actually tell the truth, which was a lot more complicated — that he was really good, and he tried really hard and failed, and then couldn’t cope with the failure,” Miller explains. And that’s just one of the points of tension in the book that makes Weaver such a fascinating subject.

“I probably didn’t hammer this enough in the book: I think his personality as a young player was part of the problem, that he couldn’t handle failure. After that episode [in 1952 Spring Training], when he was a player-manager, he was being heckled by the other team in this minor league game in Georgia, and he took a right turn by himself into the dugout and tried to fight the entire opposing team, and got the crap beat out of him… ended up in a coma basically, and he never again started another brawl. But I think that shows you what kind of temper he had — and personally, I don’t think his makeup was very good, to use the modern baseball language. I think he matured and grew, and that’s also what makes him a great character.”

Last year, I read a story about when Weaver — with the benefit of expanded rosters in September — would start left-handed power-threat Royle Stillman at shortstop vs. right-handed starters on the road. I’ll give you a moment to process that.

On six occasions in 1975, while the Orioles desperately pursued the first-place Red Sox, Weaver benched Mark Belanger, the light-hitting Gold Glove shortstop, to start the game.

I was thrilled that Miller addressed the strategy in The Last Manager, referring to the tactic as “reverse pinch-hitting.” Thinking like Weaver, Miller adds, “It’s intuitive intelligence… The reasoning is that a pinch-hit at-bat is worth as much in the first inning as it is in the ninth inning. So why wouldn’t you just have a pinch hitter lead the game off, then you put your defensive-first shortstop in?” It’s not much different than the opener trend — employing a relief pitcher to start the game and match up against the top of an opponent’s lineup — that teams like Tampa Bay leveraged not too long ago.

Weaver’s relevance in today’s game is tacitly argued by Miller over the course of the book. In the case of Stillman, the manager turned to an analytically driven strategy to optimize run production. Over a small sample size, Belanger’s replacement went 3-for-6. Weaver, though, wasn’t convinced that his lineup machinations were worth the trouble and essentially gave it up after the ’75 season. Perhaps he was aware that it embarrassed his everyday shortstop, and that Belanger’s emotional well-being was more important to the team than a very slight advantage in an already bleak situation. Statistically minded and sensitive to the clubhouse? See. We need Earl more than ever today.

The Last Manager will fascinate and entertain you through the final weeks of Spring Training, it will prepare you for Opening Day, and it will enhance the way you watch baseball this season. Wherever you’re managing from, do it with Weaver and The Last Manager by your side.

WTP offers free and paid subscriptions. Sign up now and never miss a word. Plus, I have so much more from my conversation with John W. Miller and so many more highlights from the book. Stick around for Bob Bonner, Steve Dalkowski, and their connection to Bull Durham.

This story sounds very interesting. I’ll be sure to check it out!

I trust the story of how Dan Stanhouse got the nickname “Fullpack” is included! And the legendary battles with Jim Palmer. “The only thing Earl knows about pitching is he couldn’t hit it!”